The Securities Act of 1933

Now that you’ve raised your fund, you need to stay out of jail. I’m (mostly) kidding. In this part of the book, I’m going to provide an overview of key laws governing investment funds and syndications to help you stay compliant.

First up is the Securities Act of 1933. The big one! The Securities Act applies to anyone selling securities. And guess what? You’re almost certainly selling securities.

WHAT IS A SECURITY?

In typically dense fashion, the Securities Act defines “security” as follows:

The term “security” means any note, stock, treasury stock, security future, security-based swap, bond, debenture, evidence of indebtedness, certificate of interest or participation in any profit-sharing agreement, collateral-trust certificate, preorganization certificate or subscription, transferable share, investment contract, voting-trust certificate, certificate of deposit for a security, fractional undivided interest in oil, gas, or other mineral rights, any put, call, straddle, option, or privilege on any security, certificate of deposit, or group or index of securities (including any interest therein or based on the value thereof), or any put, call, straddle, option, or privilege entered into on a national securities exchange relating to foreign currency, or, in general, any interest or instrument commonly known as a “security”, or any certificate of interest or participation in, temporary or interim certificate for, receipt for, guarantee of, or warrant or right to subscribe to or purchase, any of the foregoing.

15 U.S. Code § 77b—Definitions; promotion of efficiency, competition, and capital formation | U.S. Code | US Law | LII / Legal Information Institute.

To help refine the statutory definition, the courts have developed a couple of common tests.

THE “HOWEY TEST”

The famous Howey Test lays out the four main factors of an “investment contract” (which is a common type of security):

- An investment of money

- In a common enterprise

- With the expectation of profit

- To be derived from the efforts of others

SEC v. W.J. Howey Co. | 328 U.S. 293 (1946) | Justia U.S. Supreme Court Center.

There are other tests for other types of securities, but this is the one you’ll hear people talking about the most. In case you weren’t sure, passive interests in funds and syndications (which you’ll sell to LPs) fit squarely within the Howey Test’s definition of securities.

THE REVES TEST

The other popular test is the Reves Test, which is used to determine whether a promissory note counts as a security. Feel free to go look this up in your free time, but it’s not going to be directly relevant to us for the purposes of this book.

Reves v. Ernst & Young | 494 U.S. 56 (1990) | Justia U.S. Supreme Court Center.

THE PRACTICAL BOTTOM LINE

I’ve discussed these tests for the legal nerds out there. In practice, you can safely assume that if you are soliciting passive investors (publicly or privately) to invest in your fund, syndication, or other pooled investment vehicle, you are selling securities.

On the other hand, if you are merely seeking a business partner (or to form a joint venture where both parties have significant control over the investment), you’re likely not selling securities. But double check with your lawyer. Every situation is different.

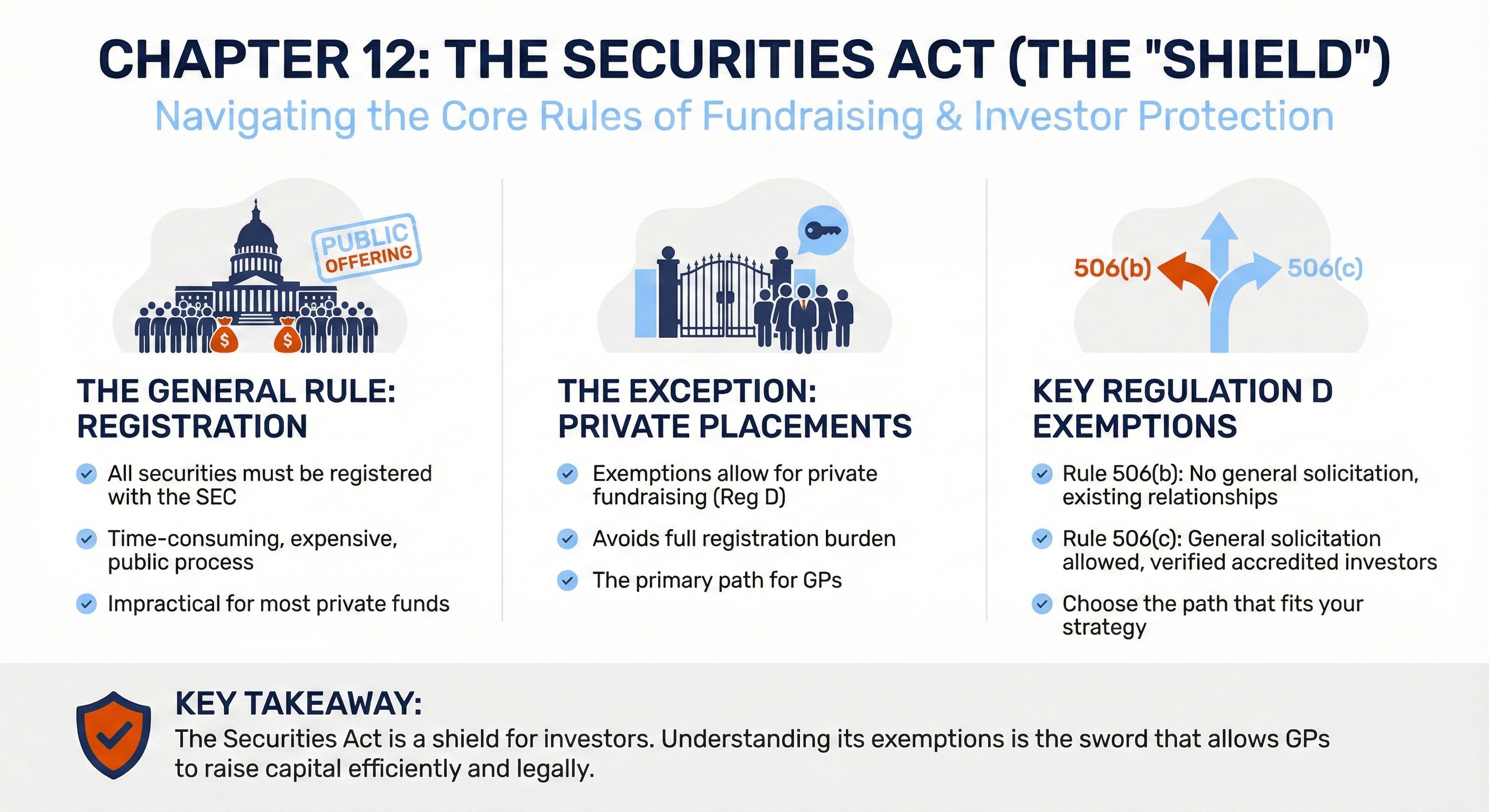

WHAT MUST YOU DO IF YOU’RE SELLING SECURITIES?

As a general rule, if you are selling securities, you must either:

- Register: Register the securities with the SEC

- Find an Exemption: Sell the securities pursuant to an exemption from SEC registration

Registering the securities means issuing an initial public offering (or other take-public transaction) for your fund or syndication. Unless you are raising an utterly massive investment vehicle, you do not want to go public. Way too burdensome and expensive. Too much lawyer time for your own good. You want an exemption. One hundred percent of my clients use an exemption.

WHAT EXEMPTIONS FROM SECURITIES REGISTRATION ARE THERE?

Common exemptions to SEC registration include:

- Regulation A: A public/private hybrid that has two tiers (Tier 1 for simpler raises of up to $20 million in a twelve-month period, and Tier 2 for more complex raises of up to $75 million in a twelve-month period). Regulation A requires significant disclosure and process.

- Regulation S: An exemption for sales of securities outside the US.

- Regulation CF: The “crowdfunding” exemption that allows you to raise up to $5 million in a twelve-month period. It has investment limits and other technical requirements.

- 4(a)(2): An exemption for transactions by an issuer of securities not involving a public offering.

While these exemptions are all well and good, they’re too expensive, complicated, or uncertain for most investment funds and syndications. Instead, most GPs turn to the golden child: Regulation D.

REGULATION D

Regulation D is a magnificent law that provides a “safe harbor” for certain securities offerings. There are multiple flavors to Regulation D. The two most typical options for investment funds and syndications are Rule 506(b) and Rule 506(c). They’re easy to use, do not limit the amount of money you can raise, and require less lawyer time (and money) than the other options, so long as each investor you accept is an accredited investor.

17 CFR § 230.506—Exemption for limited offers and sales without regard to dollar amount of offering. | Electronic Code of Federal Regulations (e-CFR) | US Law | LII / Legal Information Institute.

WHAT IS AN ACCREDITED INVESTOR?

There are many ways to be accredited, but the most common are:

- Individual (Income): An individual with $200,000 in annual income (or $300,000 joint income with a spouse) for the last two years with an expectation to continue earning income above the threshold.

- Individual (Net Worth): An individual with a $1 million net worth (excluding the value of the primary residence and any debt thereon).

- Individual (Tests): An individual with certain securities licenses (such as Series 7, Series 65, or Series 82).

- Entity (Assets): An entity with at least $5 million in assets.

- Entity (All Owners Accredited): An entity where each of the equity owners is an accredited investor.

Also, if you’re the GP of a fund or syndication, you’re an accredited investor with respect to that particular fund or syndication. Your fund’s sub docs will have a full list of options for becoming an accredited investor for LPs to choose from. For more options, check out the SEC’s website.

SEC.gov | Accredited Investors.

Alright, now that we understand what makes an investor accredited, let’s evaluate 506(b) and 506(c) in detail.

RULE 506(B)—“506 BE QUIET!”

506(b) is a great option for the true “private placement” of securities. This is the version of fundraising most people are used to.

Advantages of 506(b)

The beauty of 506(b) is you can have investors self-certify whether they’re an accredited investor in their sub docs. All you have to do is ask (assuming you don’t have reason to believe they’re lying). This is very simple and low friction.

Disadvantages of 506(b)

You must have a preexisting relationship with each investor. Friends, family, etc. In other words, you have to know all your LPs before they invest. To use 506(b), you cannot fundraise in the following ways:

- Podcasts

- Twitter (or X, if I must)

- Advertisements

- Fund-related speeches at conferences

- Blasting an email to a bunch of people you don’t know

- Running around Times Square with a sandwich board

Basically, you can’t talk about your fund in public. So…what can you talk about?

In general, it’s best to avoid any mention of the fund or fundraising. You can potentially offer your views on the market but don’t solicit investors or even suggest you’re raising money. It’s a gray, murky analysis. I counsel clients that it’s better to be safe than sorry and advise erring on the side of saying less rather than more. When in doubt, ask your lawyer.

⚠ FUND TRAP #12: ACCEPTING NON-ACCREDITED INVESTORS IN A 506(B) OFFERING

506(b) technically allows you to have up to thirty-five nonaccredited investors. Many lawyers will tell you that. What many lawyers forget is that, pursuant to Section 502(b), if you accept even one nonaccredited investor, you must do a bunch of extra disclosure. I was considering listing the full cornucopia of requirements here but decided to save a forest.

Basically, if you accept a nonaccredited investor, you need a mountain of disclosure, similar to what you would need to disclose if you were using Regulation A. For this reason, many funds accept only accredited investors even if they use Rule 506(b). Please read this section again if you’re planning to use 506(b). Lawyers routinely don’t know this part of the law and put their clients at risk.

At a previous firm, we had a client who absolutely insisted he wanted to accept non-accredited investors (against our advice). He ended up spending five figures and untold hours on the additional disclosure. It’s just not worth it for the vast majority of GPs.

RULE 506(C)—“COME SEE OUR FUND!”

506(c) is a newer creature (born in 2013) that is becoming increasingly popular. It allows for the public solicitation of investors.

Advantages of 506(c)

506(c) is great because you don’t need to worry about what you say in public. Go ahead and talk about your fund or syndication wherever you want. You can post about fundraising on the internet. You can go on podcasts. You can even advertise (though I’ll leave it to you to decide whether you think that’s a good idea from a reputational perspective).

Disadvantages of 506(c)

Unlike 506(b), you must “take reasonable steps to verify” that 100 percent of your investors are accredited. You can do this by getting a letter from each investor’s attorney, CPA, or financial advisor verifying accreditation. You can also hire a third party to verify investors for you. Several online services will do this for around $50. Not bad at all. In a pinch, you can also review investor tax returns to verify income.

Just before this book was finalized by the publisher, the SEC issued a “no action letter” suggesting that a GP could assume that investors are accredited if the following requirements are met:

- Minimum Investment: The minimum check size is $200k for individuals and $1 million for entities.

- LP Representations: The LP represents that it is not financing any portion of its capital commitment.

- GP Representations: The GP represents that it isn’t aware of any untrue statements of fact by the LP regarding its accredited status.

If the LP is an entity that is accredited only because all of the LPs’ owners are accredited, then each of the above applies to each of the LP’s underlying equity owners.

For larger funds with larger minimums, this may offer an easy way to use 506(c) without explicit third-party verification. Ask your lawyer!

WHICH IS BETTER—506(B) OR (C)?

In short, the benefit of 506(c) is you can raise money publicly. The benefit of 506(b) is investors can self-certify that they are accredited without meeting the new minimum check size thresholds.

If you’re not sure which you prefer, you can switch from 506(b) to 506(c) if you change your mind mid-fundraise. However, you cannot go from 506(c) back to 506(b). No putting the genie back in the bottle, toothpaste back in the tube, rabbit back in the hat, etc. You’re locked in.

Most of your legal documents will be the same whether you use 506(b) or 506(c). The only real difference will be that you should make it clear in 506(c) subscription documents that each investor absolutely must be accredited. You can also include a form accredited-investor-verification letter the investor can send to their financial professional.

WHAT GOVERNMENT FILINGS ARE REQUIRED FOR REGULATION D?

If you use either 506(b) or 506(c), you must file a Form D with the SEC no later than fifteen days after the fund’s initial closing date. You’ll also need to make state-level Blue Sky filings. We discussed these filings in detail in Chapter 10. They’re not that bad.

BAD ACTOR DISQUALIFICATION

506(b) and 506(c) are not available to “bad actors,” as set forth in 506(d). Examples of “bad acts” include being convicted of financial crimes, being barred from being a financial professional, and generally getting into trouble with the SEC.

If you have been subject to one of these “disqualifying events,” prohibiting you from using Regulation D, you can still sell securities—it’s just more difficult. If you can’t use Regulation D, one common route is to use 4(a)(2). However, unlike Regulation D, 4(a)(2) doesn’t “preempt” state law.

If you use Regulation D, you generally don’t need to deal with state-specific versions of the Securities Act (other than making Blue Sky filings). If you use 4(a)(2), you need to research and comply with the state-specific version of the Securities Act in each state where one of your investors is based. Regulation D is much easier to work with than 4(a)(2).

NO BAMBOOZLING THE PUBLIC

No matter how you sell securities, Regulation D or otherwise, you can’t lie. More specifically, Rule 10b-5 of the Securities Exchange Act prohibits fraud, material misstatements and/or omissions, and other methods of deceit in connection with the sale or purchase of securities. Court cases have held that private citizens (as well as the SEC) can go after issuers of securities (including fund managers) for these actions, which are generally referred to as securities fraud.

Please, don’t commit fraud. You should have your lawyer review all your marketing materials (such as your marketing deck and PPM) to ensure you aren’t overpromising or misrepresenting anything. And, for the love of funds, never “guarantee” returns.

Next up, we’re going to review the second big law governing investment funds and syndications: the Investment Company Act.

More Fundamentals Chapters

Let's Build Something Together

Please provide some background on yourself, your track record (if applicable), and your goals. We're excited to get started.