How Do You Distribute Money to Investors Using a “Waterfall”?

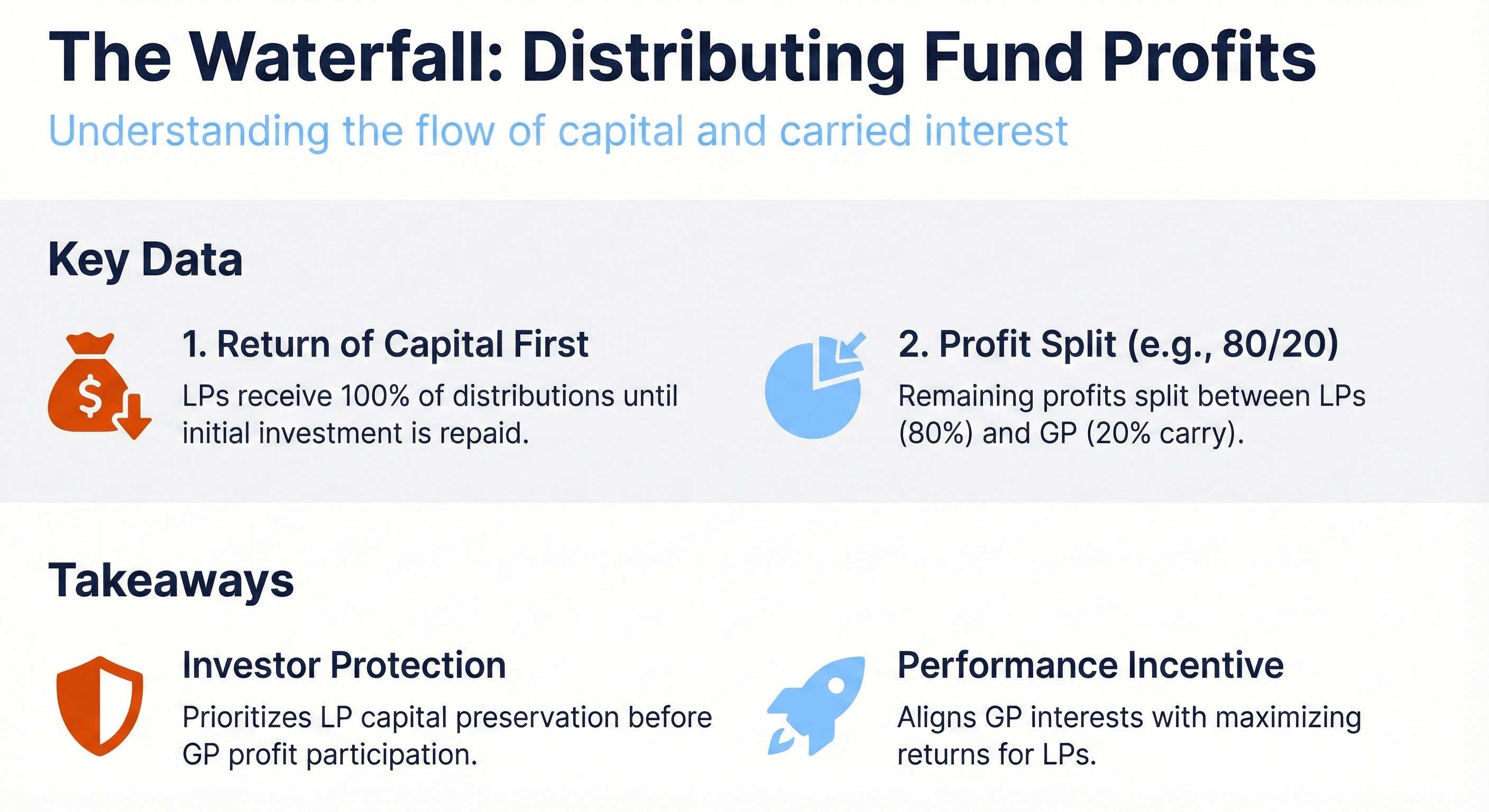

We can’t put this off any longer. It’s time to discuss the cornerstone of fund economics: the carried interest. As discussed in Chapter 2, the carried interest (also sometimes called “promote” or “incentive income”) is the GP’s share of the profits earned by the fund. Carried interest is not guaranteed. The GP earns carried interest only if the fund is profitable.

HOW IS CARRIED INTEREST TAXED?

Carried interest is typically taxed at capital gains rates, so long as certain requirements are met. We’ll discuss this more in Chapter 16. The tax treatment of carried interest is a frequent topic of heated debate by politicians, with some arguing that carried interest should be taxed at ordinary income rates (like management fees).

HOW DOES THE GP GET CARRIED INTEREST?

Every investment fund or syndication has a Distributions section in its governing documents. It’s usually somewhere in the middle. The Distributions section is often called the “distribution waterfall.” If the fund has money to distribute, the distribution waterfall dictates how the cash is divided among the fund’s LPs and the GP. In this chapter, we’ll walk through five examples of different types of distribution waterfalls.

WATERFALL WALKTHROUGH #1: SIMPLE SYNDICATION

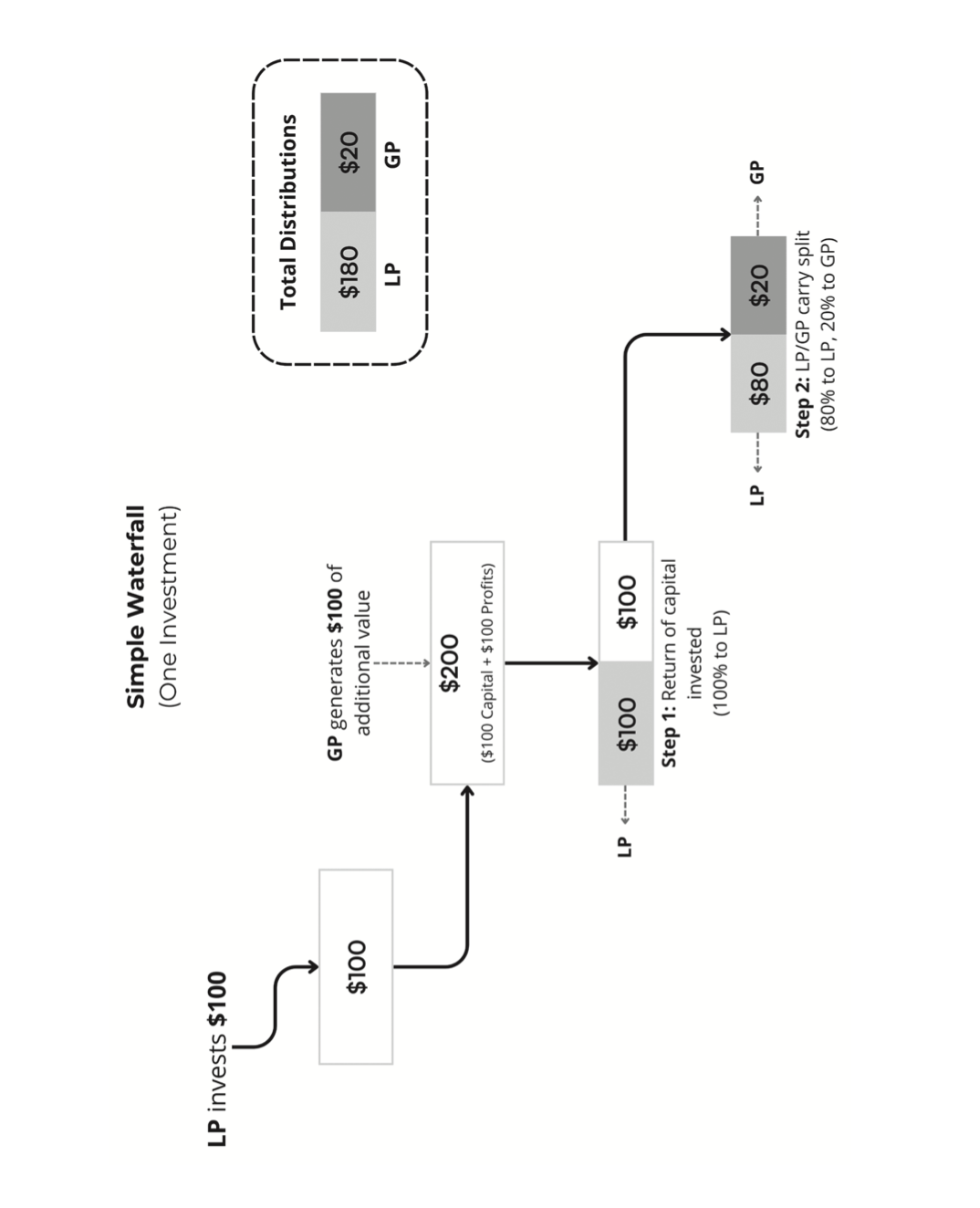

This first walkthrough is for a simple syndication.

Let’s assume the LPs invested $100. The syndication successfully sold the investment for 2x and now has $200 to distribute among the investors. The above waterfall would be common for a single-asset syndication in venture capital. This vehicle may have been formed to purchase Series A stock in a tech company.

How Would This Waterfall Be Written in a Legal Document?

This waterfall might appear in the fund’s governing documents as follows:

If there is any money to distribute, it shall be distributed as follows:

- Step 1: 100 percent to the LP until they have received distributions equal to their capital contributions; and

- Step 2: 80 percent to the LP, and 20 percent to the GP.

Note: This simplified example assumes the GP did not invest any money alongside the LPs.

How Would Money Be Distributed Among the GP and LP Pursuant to This Waterfall?

Now, let’s examine each step of the waterfall in this example:

- Capital Contribution: The initial $100 capital contribution by the LP.

- Sale: The syndication sells the assets for $200.

- Waterfall Step #1: Per the first step in the waterfall, the LP must be reimbursed the full amount of their capital contribution before any other distributions can be made—in this case, $100.

- Waterfall Step #2: After returning that $100, there’s still $100 left to be distributed ($200 – $100 = $100). Pursuant to the second step in the waterfall, profits (after the return of capital) are to be split 80 percent to the LP and 20 percent to the GP. So, we send $80 to the LP and $20 to the GP.

The $20 received by the GP is their carried interest.

CAN YOU DISTRIBUTE ASSETS OTHER THAN CASH?

Most fund agreements have a provision called “distributions in kind” that allows funds to distribute property other than cash. This is most common in funds purchasing securities and less common in funds buying illiquid assets. A multifamily real estate fund typically wouldn’t distribute apartment buildings to its investors. A private equity fund wouldn’t distribute an HVAC company.

LIMITS ON DISTRIBUTIONS IN KIND

Even in securities funds, there are typically restrictions on distributions in kind. For example, many funds limit distributions in kind during the fund’s life to freely tradeable securities (e.g., unrestricted public stock). Only after the fund’s term has ended can restricted private stock be distributed.

EXAMPLE—SERIES C PREFERRED

If a fund has Series C Preferred stock, it would typically not be able to distribute that stock in kind to investors until the end of the fund’s life…unless the underlying company goes public. If the company goes public, the fund’s Series C Preferred stock would be converted into standard common stock trading on the NYSE or NASDAQ. At that point, the fund could distribute the common stock to investors immediately. It wouldn’t need to wait until the end of the fund’s life.

In fact, LPs often prefer that funds distribute the publicly traded stock instead of holding it within the fund. Sometimes, VCs (venture capital funds) hold on to public shares because they want to (potentially) earn carried interest on the post-initial public offering appreciation. LPs don’t like that (big surprise).

AMERICAN VS. EUROPEAN WATERFALLS

Waterfall Walkthrough #1: Simple Syndication, above, explained how a single-asset syndication might distribute its profits. But how do you distribute profits if you have a multi-asset investment fund? There are two main types of distribution waterfalls used by funds with more than one asset:

- European waterfall (also known as “netted” or “crossed”)

- American waterfall (also known as “deal-by-deal”)

While I assume that, at some point, American waterfalls were common in America and European waterfalls were common in Europe, that is no longer the case. Paradoxically, most funds in the United States have a European waterfall.

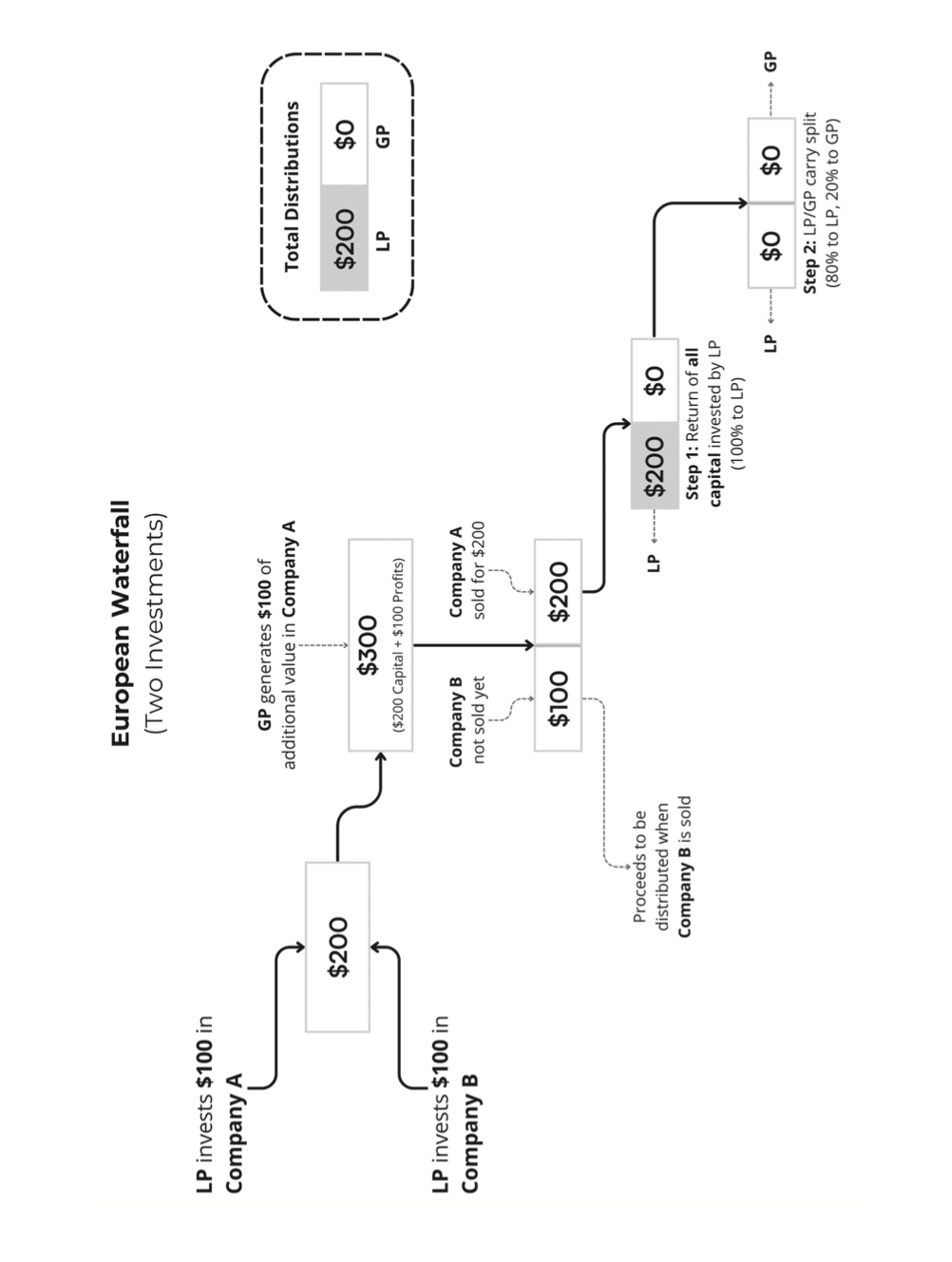

EUROPEAN WATERFALLS

European waterfalls are simple enough. All the capital contributions made by an LP are treated as one big, fungible pool of money that must be returned to the LP before the GP gets any carried interest. In other words, the capital contributions among all investments are “netted” or “crossed.”

WATERFALL WALKTHROUGH #2: EUROPEAN WATERFALL

This example assumes a very simple waterfall, which is common in venture capital funds.

How Would This Waterfall Be Written in a Legal Document?

This waterfall might appear in the fund’s governing documents as follows:

If there is any money to distribute, it shall be distributed as follows:

- Step 1: 100 percent to the LP until the LP gets a return of their capital contributions used to fund all investments; and

- Step 2: 80 percent to the LP, and 20 percent to the GP.

How Would Money Be Distributed Among the GP and LP Pursuant to This Waterfall?

Let’s walk through how the money flows in this example:

- Capital Contribution: The initial capital contributions by the LP of $200 ($100 was used to buy Company A, and $100 was used to buy Company B).

- Sale: The fund sells Company A for $200.

- Waterfall Step #1: Per the first step in the waterfall, $200 (the total capital invested by the LP) goes to the LP.

- Waterfall Step #2: We don’t have any more money to distribute, so we don’t get to the second step in the waterfall, and the GP does not get any carried interest yet. No fun!

Note that if the fund had sold Company A for more than $200, the GP would have received some carried interest. For example, if the fund had sold Company A for $225, $200 would have been returned to the LP, and the remaining $25 would have been split 80 percent to the LP ($20) and 20 percent to the GP ($5).

Assuming Company B is successfully sold for more than $0, the GP will receive carried interest from its sale (because the LP already received a total return of capital upon the sale of Company A).

Returning Capital Contributions for Fund Expenses in European Waterfalls

Returning expenses is simple in European waterfalls. In Waterfall Walkthrough #2: European Waterfall, we oversimplified Step 1, saying the LP gets back all its capital contributions used to fund all investments.

In reality, LPs get back all their capital contributions used to fund…anything. It looks something more like:

- Step 1: 100 percent to the LP until the LP gets back all their capital contributions used for any purpose; and

- Step 2: 80 percent to the LP, and 20 percent to the GP.

In other words, if an LP invests $100, $90 of which is used to fund investments, $8 of which is used to pay the management fee, and $2 of which is used to pay other fund expenses, the LP would receive the full $100 in Step 1 of the European waterfall.

AMERICAN WATERFALLS

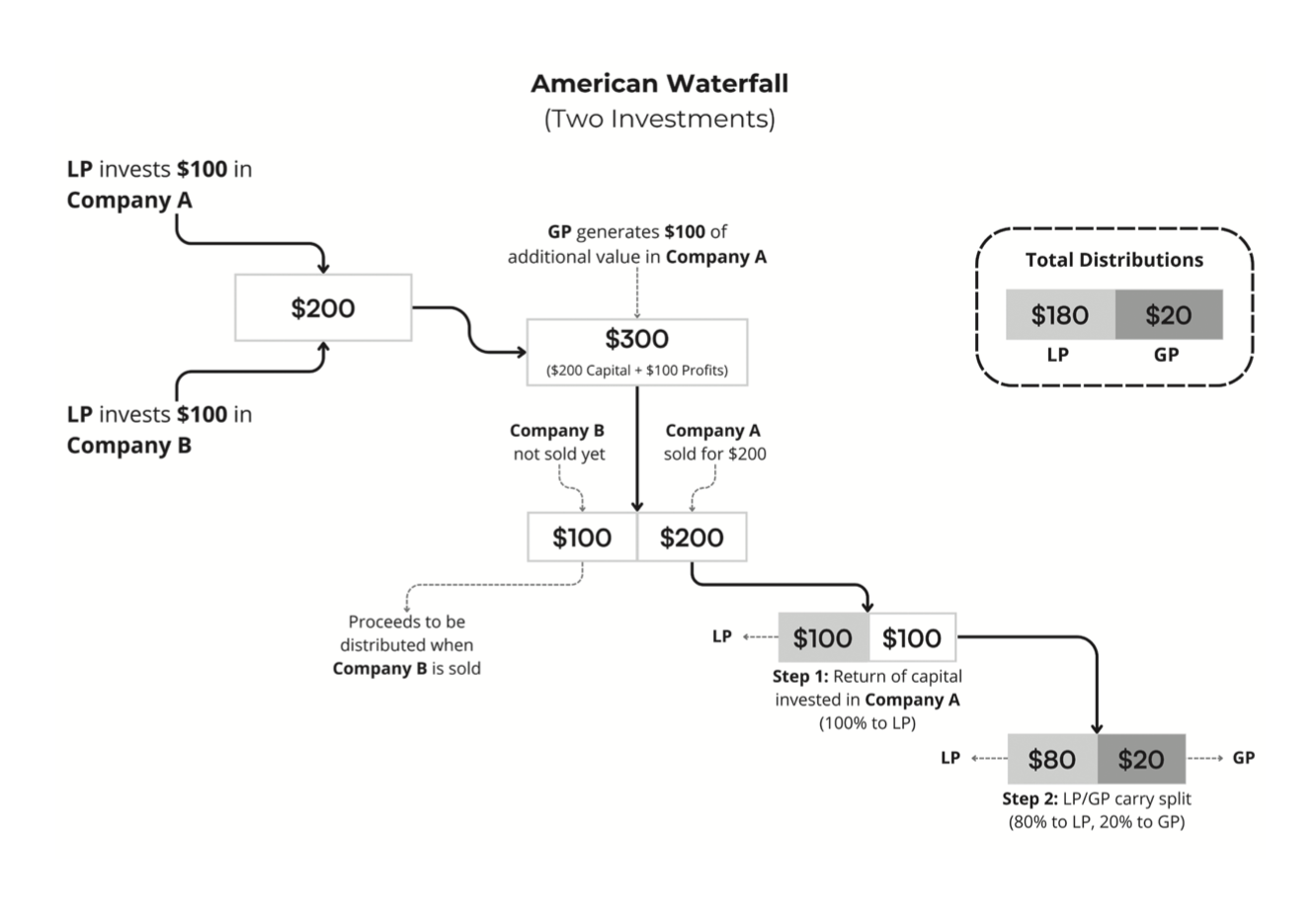

American waterfalls are a bit trickier, but I’m confident you’ll get it! Unlike European waterfalls, American waterfalls calculate returns on a deal-by-deal basis. In other words, an LP’s capital contributions used to fund different deals are segregated in the waterfall.

WATERFALL WALKTHROUGH #3: AMERICAN WATERFALL

This example assumes a simple American waterfall.

How Would This Waterfall Be Written in a Legal Document?

This waterfall might appear in the fund’s governing documents as follows:

If there is any money to distribute from the sale of an investment, it shall be distributed as follows:

- Step 1: 100 percent to the LP until the LP gets a return of their capital contributions used to fund the sold investment; and

- Step 2: 80 percent to the LP, and 20 percent to the GP.

Note that Step 1 is different than in a European waterfall! It refers to a return of capital used for the investment that was sold—not a return of capital from all investments.

How Would Money Be Distributed Among the GP and LP Pursuant to This Waterfall?

Let’s walk through how the money flows in this example (the first two bullets are the same as Waterfall Walkthrough #2: European Waterfall):

- Capital Contribution: The initial capital contributions by the LP of $200 ($100 was used to buy Company A, and $100 was used to buy Company B).

- Sale: The fund sells Company A for $200.

- Waterfall Step #1: Per the first step in the waterfall, $100 (the total capital invested by the LP to fund the purchase of Company A) goes to the LP.

- Waterfall Step #2: The remaining $100 is split 80 percent to the LP ($80) and 20 percent to the GP ($20).

As you can see, the American waterfall is better for the GP. With the exact same facts, the American waterfall yields $20 of carried interest, while the European waterfall results in a big ol’ goose egg.

Returning Capital Contributions for Fund Expenses in American Waterfalls

There are a couple of options for returning expenses in American waterfalls.

Option 1: Return All Expenses

The more LP-friendly formulation is to return all fund expenses in Step 1 of the waterfall. It might look like this:

- Step 1: 100 percent to the LP until the LP gets a return of their capital contributions used to fund the sold investment plus all capital contributions used to fund expenses; and

- Step 2: 80 percent to the LP, and 20 percent to the GP.

Option 2: Return Investment-Related Expenses

The more GP-friendly option allocates fund expenses on an investment-by-investment basis and only returns expenses allocated to the sold investment. It might look like this:

- Step 1: 100 percent to the LP until the LP gets a return of their capital contributions used to fund the sold investment plus all capital contributions used to fund expenses allocable to the sold investment; and

- Step 2: 80 percent to the LP, and 20 percent to the GP.

“Deal-by-Deal” vs. “Realized Investments” in American Waterfalls

A final wrinkle is that some American waterfalls aren’t really “deal-by-deal” after all. Instead of strictly segregating deals, the first step of these waterfalls returns all capital contributed to all fund investments that have been sold or permanently written off.

Let’s say you have five investments. You sold Investment #1 yesterday. When you sold that investment, Step 1 of the waterfall required a return of LP capital used to fund Investment #1. This is what we did in Waterfall Walkthrough #3: American Waterfall.

Today, you sell Investment #2. Now, Step 1 of the waterfall requires you to return capital used to fund Investment #1 and Investment #2—both investments have been disposed of. But you do not consider capital contributions to fund Investments #3–5 because they haven’t been sold or written off yet. You’ll deal with them later.

It’s kind of a hybrid between a netted waterfall and a true deal-by-deal waterfall. It’s basically a European waterfall but only for exited investments.

It might look something like this:

- Step 1: 100 percent to the LP until the LP gets a return of their capital contributions used to fund all investments that have been sold or completely written off plus all capital contributions used to fund expenses; and

- Step 2: 80 percent to the LP, and 20 percent to the GP.

As you can see, there are many options for American waterfalls!

SELECTING A WATERFALL—AMERICAN OR EUROPEAN?

While American waterfalls are better for GPs, European waterfalls are more common in the market. For that reason, I often advise emerging managers to go with a European waterfall. In addition, American waterfalls are more likely to result in an unfavorable clawback situation (we’ll discuss clawbacks later in this chapter). Using American waterfalls is not unreasonable, but having a European waterfall is more LP-friendly and will likely make fundraising easier.

PREFERRED RETURNS

Now that we’ve discussed European versus American waterfalls, we’re going to move on to a separate topic in investment fund waterfalls. In many funds (especially real estate and private equity funds), the waterfall has more steps than the simple two-step waterfalls we’ve discussed so far in this chapter.

After (or sometimes before) the “return of capital” step, LPs might receive a preferred return before the GP gets their carried interest. This could be the case in a syndication, a fund with a European waterfall, or a fund with an American waterfall. In the walkthrough below, the preferred return will be applied to a simple syndication (to make things as simple as possible).

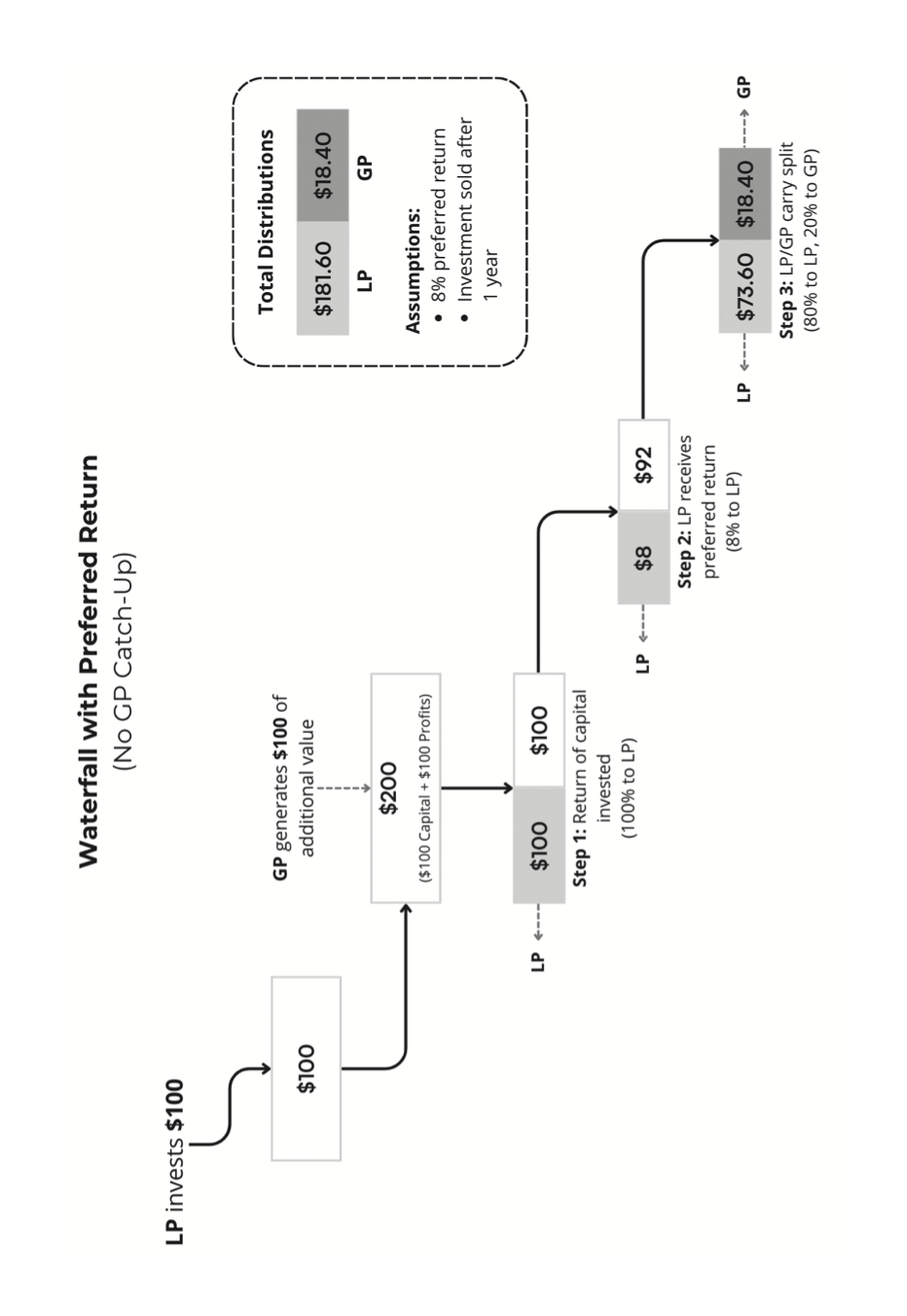

WATERFALL WALKTHROUGH #4: PREFERRED RETURN

In this example, the LP receives an 8 percent preferred return before the GP starts earning carried interest.

How Would This Waterfall Be Written in a Legal Document?

This waterfall might appear in the fund’s governing documents as follows:

If there is any money to distribute, it shall be distributed as follows:

- Step 1: 100 percent to the LP until they have received distributions equal to their capital contributions;

- Step 2: 100 percent to the LP until they have received distributions equal to 8 percent, compounded annually, on their capital contributions; and

- Step 3: 80 percent to the LP, and 20 percent to the GP.

In short, if the fund returns capital to the LP but does not exceed their contributions plus an 8 percent return, the GP does not get any carried interest.

How Would Money Be Distributed Among the GP and LP Pursuant to This Waterfall?

Let’s walk through the flow of funds in this example:

- Capital Contribution: The initial capital contributions by the LP of $100.

- Sale: The fund sells the assets for $200.

- Waterfall Step #1: Per the first step in the waterfall, $100 (the full amount of LP’s capital contributions) goes to the LP.

- Waterfall Step #2: Per the second step in the waterfall, the LP gets an 8 percent return on its $100 contribution. Here, let’s assume it’s been one year since the LP contributed the capital, so the preferred return is $8 (8 percent of $100).

- Waterfall Step #3: The remaining $92 is split 80 percent to the LP ($73.60) and 20 percent to the GP ($18.40).

In total, the LP received $181.60 (100 + 8 + 73.6), and the GP received $18.40. If there were no preferred return, the LP would have received $180 (a capital return of $100 plus 80 percent of the remaining $100), and the GP would have received $20. So, obviously, the preferred return is good for the LP.

DIFFERENT FLAVORS OF PREFERRED RETURNS

Here are a few ways preferred returns can differ from fund to fund:

- Compounded/Non-Compounded: In some funds, the preferred return compounds annually. In other funds, it is a “simple” (non-compounded) preferred return.

- Percentage: In lower-risk funds, the preferred return is often lower. For example, in a buy-and-hold multifamily real estate fund, the preferred return might be just 6 percent. In higher-risk funds, the preferred return is usually higher. For example, a development fund might have a preferred return of 12 percent.

- Positioning Within the Waterfall: Some funds have the preferred return step after the return of capital step. Others have the preferred return step before the return of capital step.

- Dual Waterfalls: Some funds have a standard waterfall, as we discussed above for dispositions (sales, refinances, etc.), but a separate waterfall for cash flow from operations. The cash flow waterfall might have no return of capital step at all. Step 1 would be the preferred return, and Step 2 would be a profit split. This is more common in buy-and-hold style funds.

GP CATCH-UPS

On to the next topic! Many funds and syndications with a preferred return also have something called a “GP catch-up” after the preferred return step in the waterfall. People always get confused by this one. Let’s start with some philosophy and then look at an example.

WHY DO YOU NEED GP CATCH-UPS?

In a distribution waterfall, the profit split is the percentage of the profits the GP is supposed to get as carried interest. Simple enough. But if you look at Waterfall Walkthrough #4: Preferred Return, the GP didn’t get 20 percent of the profits at all! The GP got 18.4 percent, even though the ultimate “profit split” was 20 percent. This is because the LP got a priority distribution (the preferred return) before the profit split kicked in.

A GP catchup is a provision that “catches the GP up” to the 80/20 profit split after the preferred return but before the official 80/20 step of the waterfall. An 80/20 waterfall can be thought of like this: “For every four steps forward the LP takes, the GP takes one step forward.” The preferred return is the LP taking their four steps forward early. The GP catchup is the GP taking one step forward before the final phase of the LP and GP taking their steps forward simultaneously. Otherwise, the GP will always be one step behind.

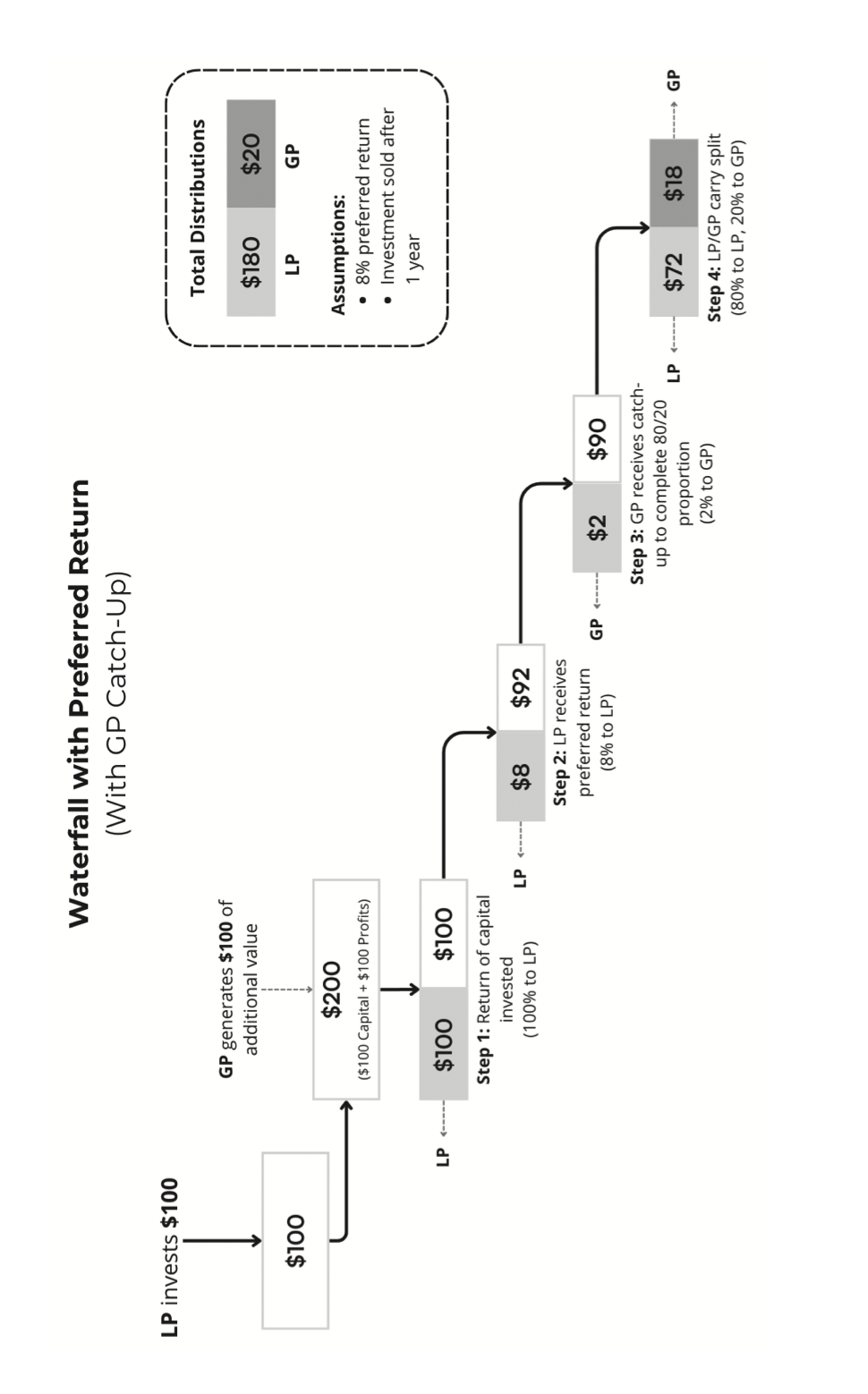

WATERFALL WALKTHROUGH #5: GP CATCHUP

Here’s the same waterfall as the previous one in Waterfall Walkthrough #4: Preferred Return, but with a GP catchup added.

How Would This Waterfall Be Written in a Legal Document?

This waterfall might appear in the fund’s governing documents as follows:

If there is any money to distribute, it shall be distributed as follows:

- Step 1: 100 percent to the LP until they have received distributions equal to their capital contributions;

- Step 2: 100 percent to the LP until they have received distributions equal to 8 percent, compounded annually, on their capital contributions;

- Step 3: 100 percent to the GP until the GP has received 20 percent of the amounts distributed pursuant to Step 2 and Step 3; and

- Step 4: 80 percent to the LP, and 20 percent to the GP.

How Would Money Be Distributed Among the GP and LP Pursuant to This Waterfall?

Let’s walk through the flow of funds in this example:

- Capital Contribution: The initial capital contributions by the LP of $100.

- Sale: The fund sells the assets for $200.

- Waterfall Step #1: Per the first step in the waterfall, $100 (the full amount of LP’s capital contributions) goes to the LP.

- Waterfall Step #2: Per the second step in the waterfall, the LP gets an 8 percent return on its $100 contribution. Here, let’s assume it’s been one year since the LP contributed the capital, so the preferred return is $8 (8 percent of $100).

- Waterfall Step #3: The GP catchup kicks in. Because the profit split in Step #4 allocates 20 percent of the profits to the GP, this step catches the GP up to 20 percent of the profits distributed so far (in Step #2 and this Step #3). Here, the GP gets $2 because $2 is 20 percent of $10—the sum of $8 (the profits distributed to the LP in Step 2) and $2 (the profits distributed to the GP in this step).

- Waterfall Step #4: Per the fourth step in the waterfall, the remaining $90 ($100 – 8 – 2) is split 80 percent to the LP ($72) and 20 percent to the GP ($18).

In total, the LP received $180 (100 + 8 + 72), and the GP received $20 (2 + 18). The GP catchup resulted in the GP getting more carried interest than they would have without the GP catchup. In fact, the GP got the same amount of carried interest as if there were no preferred return at all (as long as the fund returns at least 10 percent).

This setup results in the following:

- Poor Performance: If the fund generates less than a 10 percent return (8 percent for the preferred return and 2 percent for the GP catchup), the GP makes less money than if there were no preferred return and GP catchup.

- Good Performance: If the fund generates at least 10 percent, the GP makes the same amount of money as if there were no preferred return and GP catchup, but the LP gets the money first in time, which benefits LPs.

DIFFERENT FLAVORS OF GP CATCHUPS

Our above example has a 100 percent GP catchup, which means the GP gets 100 percent of the distributions in Step 3 until the GP has received 20 percent of the profits. Another option (which is more favorable to LPs) is to have a catchup of less than 100 percent.

For example, Step 3 could give 50 percent of the profits to the LP and 50 percent to the GP until the GP has received 20 percent of the profits. This is still better than no catchup at all from the GP’s perspective, but it’s less exciting than the 100 percent catchup. It just takes longer for the GP to catch up.

⚠ FUND TRAP #7: NOT TAKING THE WATERFALL SERIOUSLY

You’d be surprised, but some GPs don’t take sufficient care when crafting their waterfalls. Carried interest is the big reason people start a fund or syndication. GPs should carefully evaluate different waterfall options in the context of their asset class and return profile.

The waterfall also has ramifications for a GP’s public image. Do you really want to be the GP charging 50 percent carried interest? You might make excess profits in the short term, but, unless you’re Renaissance Technologies, it probably isn’t a great long-term strategy.

One time, a potential client wanted us to read their fund documents to make sure they were ok. Alas, they were not ok. The Distributions section of the LPA said: “Distributions will be made pro rata to the partners.” In other words, the provision granting the GP carried interest was…gone.

Absent! Forgotten! Missing!

The LPA is the legal document governing the relationship between the GP and the LPs, so if the carried interest isn’t mentioned in the LPA, there’s a good argument to be made that the GP isn’t entitled to it (even if carried interest was mentioned in the marketing deck or PPM). I’ll leave it to the litigators to decide how this particular case would shake out, but my warning is clear.

Do not forget to include the distribution waterfall granting the GP carried interest in your fund documents!

CLAWBACKS

Don’t break out the lobster until you’re sure you won’t have a clawback. A clawback is a provision that requires the fund to “re-test” the waterfall at the end of the fund’s life. You consider all the capital contributions and all the distributions to determine whether the GP got too much carried interest.

If the GP did get too much carried interest, they must return the excess to the fund (this is the “clawing back” of the carry).

How does a GP get too much carried interest?

Let’s say we have a very simple European waterfall with an 80/20 split after a return of LP capital and an LP commitment of $100. The GP calls $50 (50 percent of the LP’s commitment). The investment ends up being a success (a 2x multiple), and the fund distributes $100. The first step in the waterfall is the return of $50 (the LP’s invested capital). The second step of the waterfall is an 80/20 split of the profits, so $40 goes to the LP and $10 goes to the GP as carried interest.

Next, the GP calls the remaining $50 (the second half of the LP’s commitment) and invests it. The investment completely implodes and is a total loss. Nothing to distribute. Sad day.

The clawback re-tests the waterfall at the end of the fund’s life and sees $100 of total capital contributions and $100 of total distributions. What “should” have happened per the waterfall is the LP receives $100 as a return of capital and the GP gets nothing.

But wait!

The GP took $10 of carried interest after selling the first investment (before evaporating the second $50 investment). The clawback says the GP has to put the $10 back into the fund, which is then distributed to LPs.

Clawbacks can be an especially big deal for funds with American waterfalls because American waterfalls result in GPs taking carried interest earlier in the fund’s life than European waterfalls (see Waterfall Walkthroughs #2 and #3, above). So, the GP could take lots of carried interest from the good deals early on (hooray) but then have lackluster deals thereafter (boo). When the waterfall is re-tested at the end of the fund’s life, there could be a serious clawback waiting, and the GP may need to return carried interest. In fact, because of the clawback, at the end of a fund’s life, the American waterfall is no longer better for GPs than the European waterfall.

DIFFERENT FLAVORS OF CLAWBACK

In some cases, LPs might negotiate for the following:

- Personal Guarantees: Technically, the GP entity (typically an LLC) is what’s on the hook for the clawback. Sophisticated LPs may insist the individual fund principals guarantee the clawback obligation.

- Multiple Clawbacks: This isn’t super common, but some hard-negotiating LPs will require multiple clawback “tests” throughout the fund’s life. For example, a clawback after year seven and again at the end of the fund’s life.

- Carry Escrow: In some cases, the GP may be required to put a percentage of their carried interest in an escrow account so it’s easier to claw back. The GP finally gets the carried interest once it’s clear there won’t be a clawback situation.

Now that you’ve mastered distribution waterfalls, it’s time to learn where all these fund terms go. In the next chapter, we’ll discuss the legal document you need to successfully raise a fund or syndication.

More Fundamentals Chapters

Let's Build Something Together

Please provide some background on yourself, your track record (if applicable), and your goals. We're excited to get started.