Tax Laws (and How to Structure Around Them)

You’re in the home stretch! In this chapter, we’re going to discuss everyone’s favorite topic…taxes! The upside of prudent tax planning is simple: both GPs and LPs get to keep more money without getting into trouble with the taxing authorities.

This chapter was co-authored by Adam Krotman, an excellent tax lawyer who our firm works with on many funds and syndications.

WHY DO INVESTMENT FUNDS INVEST IN TAX STRUCTURING?

The four main tax-related goals of GPs and LPs include the following:

- Minimize Taxable Income: Not all “income” is taxable (e.g., gain on the sale of “qualified small business stock” may not be taxable). Plus, not all costs are immediately tax-deductible—see the section on separating the GP and the ManCo below.

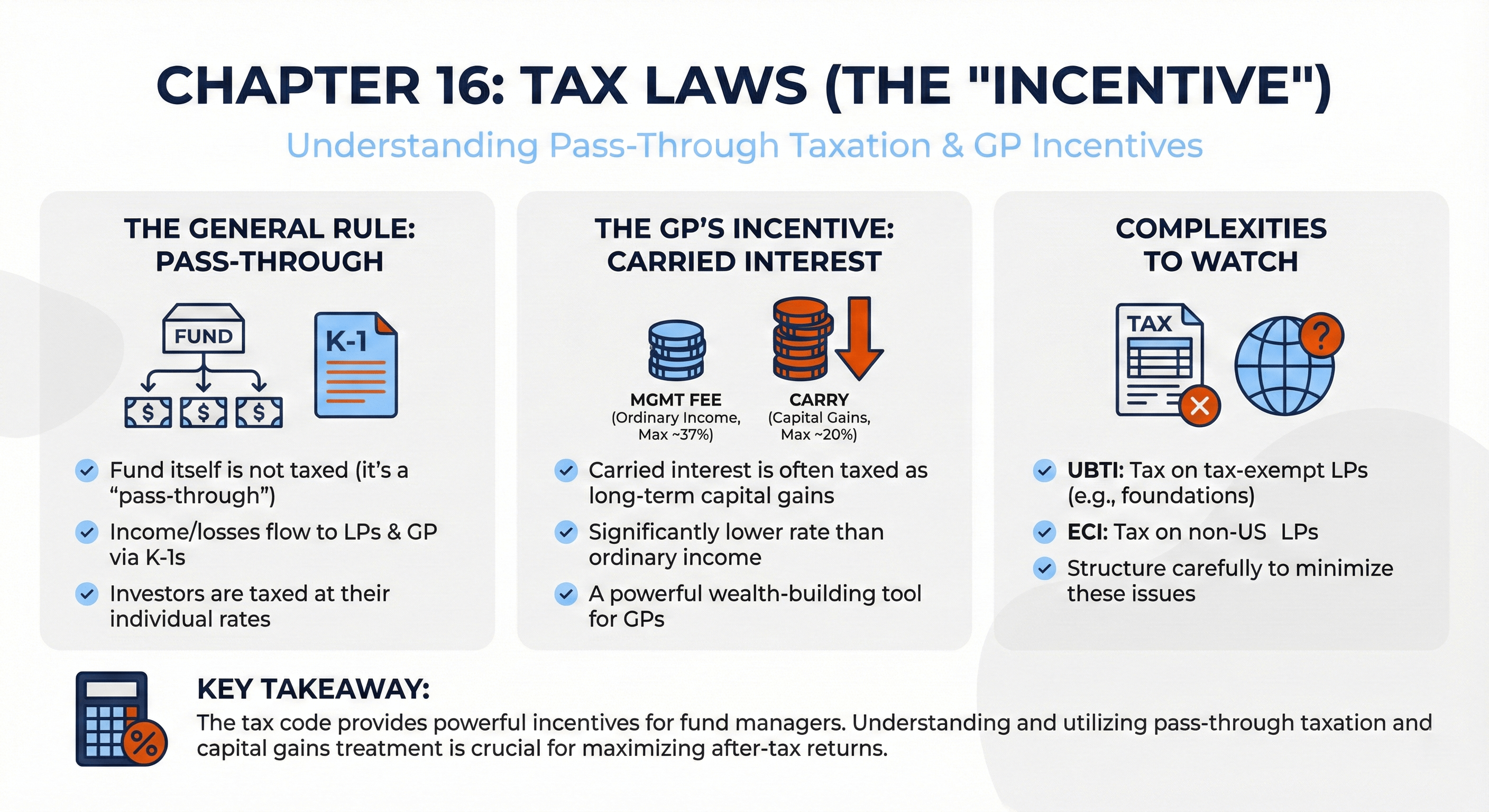

- Minimize Tax Rates: Different types of income are taxed at different rates (e.g., carried interest income may be taxed at preferential long-term capital gain rates, while management fees are taxed as ordinary income).

- Defer Taxes as Long as Possible: You are generally better off deferring taxes into later years—time value of money and all that. Plus, if you defer long enough, you may avoid the tax altogether, and your heirs might receive a stepped-up basis down the line.

- Tax Risk and Administration: You’ll need to determine the balance that’s right for you between minimizing taxes, minimizing audit risk, and maintaining a reasonable budget for your CPA and tax lawyer.

WHICH TAXES ARE APPLICABLE TO INVESTMENT FUNDS AND SYNDICATIONS?

There are three main categories of taxes that may impact your fund’s tax structure. The main concern for US-based funds and syndications is US federal income tax, but some other taxes also merit discussion.

US Federal Income Tax

As of this writing, the current top marginal tax rate for US individuals on ordinary income is a whopping 37 percent (currently scheduled to increase to 39.6 percent in 2026…we’ll see what Trump does). The top marginal tax rate for US corporations is 21 percent. Finally, the top marginal tax rate for long-term capital gains and qualified dividends is effectively 23.8 percent.

Ordinary income includes most people’s compensation, such as salaries and wages, and most businesses’ operating income. For GPs, management fees are typically taxed at ordinary income tax rates. For LPs, income taxes affect certain types of income a fund may generate, such as interest from debt securities or hedge fund income from sales of securities held less than a year (technically, this is “short-term capital gain,” which is generally taxed at the same rate as ordinary income).

Long-term capital gains include sales of assets held for investment that satisfy certain holding periods and other requirements. For funds, this often includes the sale of portfolio company equity or real estate assets held longer than a year (however, for the GP’s carried interest, the holding period requirement for long-term capital gains treatment is three years).

As a super-bonus for venture capital (and some private equity) funds, portfolio company equity held for more than five years may be eligible for the “qualified small business stock” (QSBS) exemption, under which up to $10 million of gain (sometimes even more!) per investor (and possibly per principal) from the sale of the equity may be 100 percent exempt from US federal income tax.

US State and Local Taxes

State and local tax rules often mostly mimic the federal tax rules, and planning for these taxes typically takes a backseat to planning for the US federal income tax. However, they can be substantial in certain jurisdictions and impact structure.

For example, special New York City tax rules drive many New York City-based principals to form one entity to receive the management fee and another to receive the carried interest. The application of state and local taxes usually depends on where the fund management team operates, investors reside, and/or portfolio assets are located.

Ex-US Taxes

Funds with GPs or LPs who reside and/or operate abroad or portfolio assets located offshore should be extra careful about ex-US taxes. Additionally, some funds with special structuring may have one or more entities formed in an offshore jurisdiction, such as the Cayman Islands, in which case tax planning is needed to minimize taxes in these offshore jurisdictions.

WHAT DETERMINES INVESTMENT FUND TAX STRUCTURE?

Four factors play a big role in determining the tax classifications and jurisdictions of the various entities in your fund’s structure.

Fund Type and Strategy

Tax treatment and structure differ substantially across different types of funds, such as venture capital, real estate, private equity, and hedge funds. Key considerations include the anticipated asset mix, asset holding periods, income stream sources, and nature and geographic situs of fund management-team activity.

LP Base

Different “tax types” of investors are taxed differently and therefore have different tax structuring needs. Common investor tax types include:

• High net worth US taxable individuals and family offices

• Institutional US-taxable investors, such as corporate venture arms

• US tax-exempt investors, such as IRAs, private pension funds, and endowments

• “Super” tax-exempts, such as state and local government agencies and instrumentalities, including public pension funds

• Non-US investors, such as non-US individuals and sovereign wealth funds

Assets Under Management

Tax structures vary significantly in complexity, cost, and administrative burden. The right structure for a $10 million loan-origination fund may differ dramatically from a $1 billion fund in the same asset class.

Risk Tolerance

Given their complexity and uncertainty, taxes can be viewed as another type of business risk to manage. A good tax practitioner will help tailor the tax structure to the risk tolerance of the GP and LPs.

TAX TREATMENT OPTIONS

Now, let’s discuss the “tax treatment” you might choose for each legal entity in your fund’s structure. But first, let’s clear something up. Tax structuring can get confusing because sometimes an entity’s “legal” type is different from its “tax” type.

For example, an entity formed as a Delaware LLC may be classified for US federal income tax purposes as a partnership, a disregarded entity, a C-corporation, or an S-corporation! For some non-tax entities, the tax entity classification is elective. For others, it’s mandatory.

Examples of forms you can use to change the tax classification of entities include Form 8832 (general tax election form) and Form 2553 (electing S-corporation status).

PASS-THROUGH ENTITIES (FOR TAX PURPOSES)

Pass-throughs include partnerships, disregarded entities, and S-corporations. Most pass-through entities in fund structures are “partnerships” or “disregarded entities.” Let’s look at two key characteristics of pass-through entities.

Single-Level Taxation (i.e., No Double Taxation)

Pass-through entities generally do not pay tax at the entity level—rather, the income or loss “earned” at the entity level “passes through” to the entity’s owners and is allocated among them according to their ownership interest. For a fund, this is a complex allocation based on the investor’s and principal’s rights to distributions (i.e., the “distribution waterfall” discussed in Chapter 7).

Entities taxed as partnerships send K-1s to their “partners” each year detailing their allocable tax items. Then, the partners integrate these K-1s into their personal tax returns. Depending on the information in the K-1, the partners might pay tax on allocable income/gain or reduce taxable income using allocable losses.

Character and Activity Pass-Through

Pass-throughs can “pass through” the character of income, gain, or loss to their owners (including long-term capital gains, dividends, and QSBS). The activity of a pass-through can also attribute to its owners—this can be especially important for non-US investors. In short, this could cause non-US investors to be treated as engaged in a US trade or business and may force them to file a US tax return (rarely a welcome task).

Boo! Beware of “Phantom Income”

Phantom income is a spooky business. In a particular year, a pass-through entity might earn income it does not actually distribute to the partners. In this case, the owners may owe taxes on this “phantom income” without receiving cash to pay it.

Phantom income can arise for a number of reasons, including reinvestment of earnings, the establishment of reserves, or circumstances that produce taxable income without any liquid cash (e.g., deemed interest on certain debt instruments). In many cases, funds include special tax distribution provisions to help avoid this unpleasant result (discussed further below).

C-CORPORATIONS (FOR TAX PURPOSES)

Alright, let’s move on to C-corporations.

Double Taxation

The big downside to C-corporations is “double taxation.” First, the C-corporation may owe taxes at the entity level. The current top marginal US federal income tax rate on C-corporations is 21 percent. Next, a second level of tax may apply to the C-corporation’s equity owners when they receive distributions or sell their equity in the C-corporation.

Character and Activity Blockers

Character and activities generally do not pass through to C-corporation owners. Ordinary and capital gains income is taxed at the same C-corporation tax rate, and activities like US trade or business activity are “blocked” from attribution to non-US owners, which is why C-corporations are sometimes referred to as “blockers” in fund tax world.

US funds and syndication don’t use C-corporation entities nearly as often as pass-throughs. However, C-corporations may be helpful in certain special scenarios, such as in “blocker” tax structures to accommodate non-US and/or US tax-exempt investors.

US VS. NON-US ENTITY TYPES

Pass-through entities and C-corporations may be US or non-US entities. Countries generally have different flavors of each.

In general, US entities are cheaper and easier to form and administer than most non-US entities. For that reason, the US (and Delaware in particular) is a popular jurisdiction for funds and syndications.

However, in some scenarios, tax savings may lead funds to set up non-US entities (taxed as pass-throughs or C-corporations depending on the circumstances).

A TYPICAL TAX STRUCTURE FOR AN INVESTMENT FUND

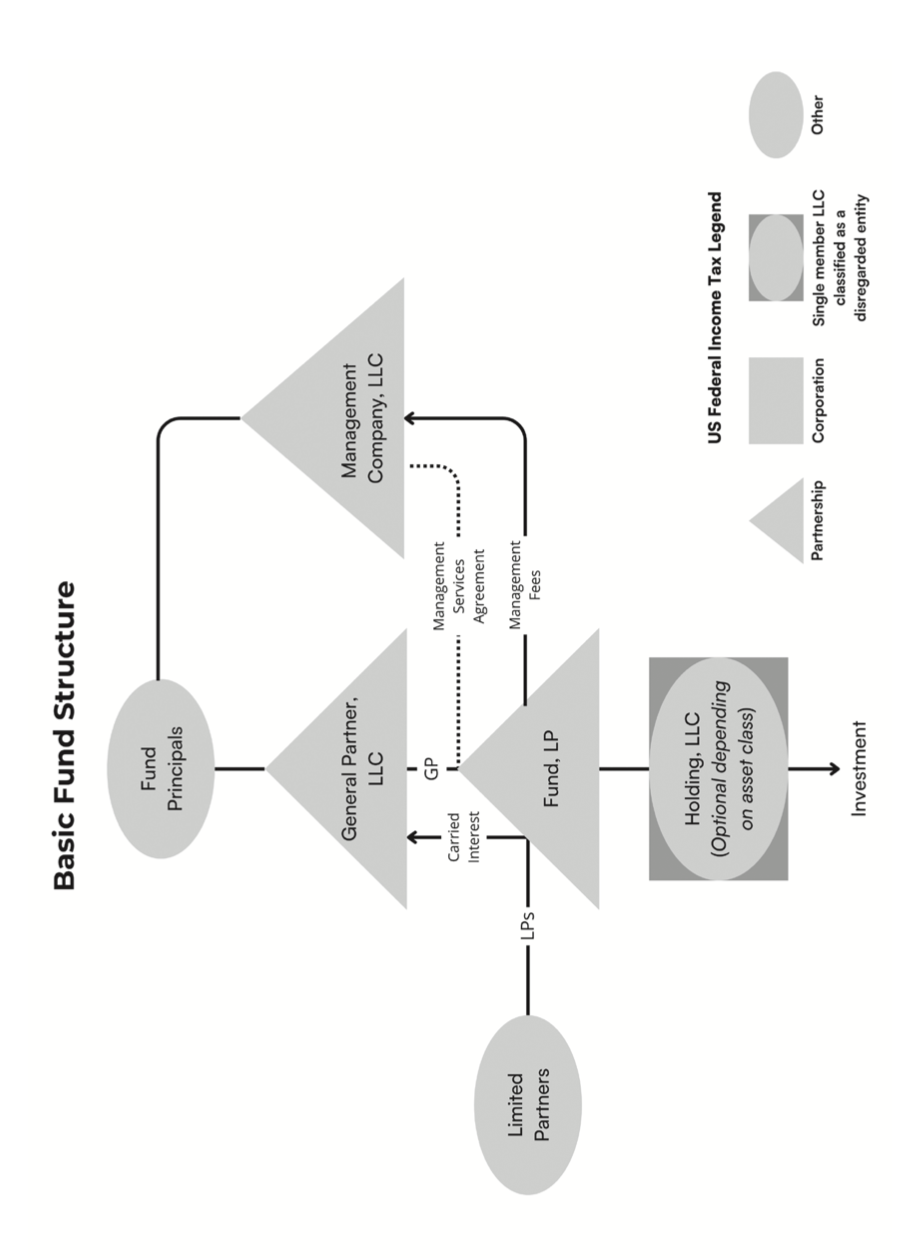

A simple fund with US-based GPs, LPs, and investments might look something like the following graphic. For reference, the following might be for a real estate fund or syndication (which is why there’s a property company to hold real estate).

In this structure, the fund, GP, and ManCo are all “pass-through” entities for US federal income tax purposes, which avoids double taxation and passes through the character of any underlying income taxed at preferential rates, such as long-term capital gain or QSBS, to the ultimate owners.

Let’s examine each entity in our structure in detail.

FUND, LP (PASS-THROUGH)

Investors invest in the fund, which in turn invests in portfolio assets directly or through other subsidiary entities. In this example, the fund invests in real estate through a wholly owned LLC (taxed as a pass-through entity). The fund’s principals also hold an equity interest in the fund indirectly through the GP.

The fund is the entity that directly earns taxable income from portfolio assets and incurs tax expenses, such as the management fee. The fund entity pays no fund-level taxes itself and instead allocates tax items of income or loss to the LPs and GP each year in rough parity to their respective distribution rights. Gains and losses will show up on the K-1s issued after the end of each year.

The “type” and amount of income or loss will vary significantly among different fund types and over the life cycle of a fund. For example, high-frequency hedge funds tend to generate large amounts of short-term capital gain and loss each year. On the other hand, venture capital funds often generate losses for several years and then (hopefully!) long-term capital gains or QSBS when they exit portfolio companies.

Some funds, such as venture capital funds, are highly limited in the ability of GPs or LPs to use tax losses, which are often permanently disallowed under current law. Others, such as hedge funds and real estate development funds, provide more flexibility to utilize tax losses. This feature relates to special rules that limit taxpayers’ ability to use investment-related expenses and may change in 2026, when certain provisions of the 2017 tax act (TCJA) are set to expire. Different funds are treated differently under these rules depending on whether they are deemed engaged in mere passive investment or a “trade or business” for tax purposes.

GENERAL PARTNER, LLC (PASS-THROUGH)

The general partner (GP) is the entity through which the principals hold an equity interest in the fund. GPs have both a capital interest (received for the principals’ investments in the fund) and a carried interest (the GP’s extra share of the profits for managing the fund) in the fund.

Like the fund, the GP’s pass-through nature means the GP itself pays no tax. Instead, they pass through the income or loss (and related character) to the principals.

Structuring the carried interest as an equity interest in the fund is the “magic” mechanism by which principals convert the carried interest from what would be ordinary income if received via a contractual fee for services into potential capital gains or other tax-preferred income.

To accomplish this objective, the carried interest must be carefully structured so that, among other things, (1) it is an interest only in the future profits of the fund (after a return of capital) and (2) certain three-year holding-period requirements are met for the underlying asset generating the income.

A failure to satisfy the above conditions can have catastrophic results for the principals, including potential “phantom income” taxed at ordinary income rates at the time the carried interest is granted (or vests). This can happen if the carried interest is determined not to be a so-called “profits interest” for US federal income tax purposes. Make sure to work with a good tax lawyer so this doesn’t happen!

MANAGEMENT COMPANY, LLC (PASS-THROUGH)

The management company (ManCo) is often owned by the same people who own the GP. Rather than an equity interest in the fund, the ManCo typically has a management agreement with the fund requiring the fund to pay the ManCo a periodic fee for its investment-management services.

The ManCo typically employs the investment team and incurs expenses that are not allocated to the fund. Examples include salaries, office rent, and other overhead.

Just like the fund and GP, the ManCo pays no tax at the entity level and passes through income and loss to its owners. However, the ManCo owners don’t get preferential long-term capital gains treatment—the fee income earned by the ManCo (management fee, other fund fees, and possibly portfolio company fees) is generally taxed at ordinary income rates.

On the other hand, unlike fund expenses (which have significant restrictions on deductibility), ManCo expenses, like salaries, professional service fees, and overhead, are typically deductible against fee income. As a result, many fund managers can limit (or even eliminate) net tax from the ManCo.

THE TAX REASONS TO SEPARATE THE GP FROM THE MANCO

It’s often preferable from a tax perspective to split up the ManCo and the GP for at least three (and sometimes four) reasons:

- Deductibility of Expenses: Separating the entities mitigates the risk that ManCo-related expenses get commingled with GP expenses and/or allocated to the GP’s equity interest in the fund. Such a misallocation of expenses to the GP equity interest could delay or entirely disallow the utilization of certain expenses that would normally offset ManCo fee income as it is earned. In short, misallocation could create excess tax liability and possibly “phantom” income, where owners have a tax liability without the net cash to pay the taxes.

- Employee Matters: Separating the entities facilitates grants of carry equity from the GP to ManCo employees without causing the employees to lose their ManCo W-2 status and related access to certain fringe benefits.

- Future Planning: Separating the entities can facilitate future tax planning in connection with potential third-party investments, insider sales, and other changes in entity ownership.

- State or Local Tax: Certain state and local jurisdictions have special tax regimes that drive GPs and ManCos apart. For example, funds with New York City–based principals often divide ManCo and the GP into separate entities to mitigate the impact of the dreaded New York City “unincorporated business tax,” which can impose an extra 4 percent on income or gain.

Aside from tax matters, fund managers also split up the GP and ManCo to segregate assets and liabilities. As discussed in Chapter 2, the ManCo typically lasts forever, while a new GP is formed for each new fund.

SPECIAL CONSIDERATIONS FOR TAX-EXEMPT INVESTORS

The US tax code exempts certain entities from US federal income taxes (and for some, allows donors to deduct the value of their monetary contributions). These entities are broadly referred to as “US tax-exempts” or “tax-exempts” and include charities, foundations, IRAs, private pension funds, and university endowments.

Investment funds often target tax-exempt LPs. Many tax-exempts supplement their donor contributions and grants with investment income. Some also like writing big checks to funds.

WHAT IS UBTI?

But tax-exempt LPs must be careful—not all passive investment income is exempt from taxation. While rules vary, most tax-exempt LPs are subject to US federal income tax on “unrelated business taxable income,” or “UBTI,” which they must report on their tax returns.

In extreme cases, too much UBTI can cause certain tax-exempts to lose their tax-exempt status, which would be disastrous for the tax-exempt LP (and not great for any donors planning to deduct charitable contributions).

MOM, WHERE DOES UBTI COME FROM?

On a high level, income or gain is UBTI if it is earned from:

- A trade or business

- Regularly carried on

- That is not substantially related to the tax-exempt investor’s purpose

For example, let’s say a tax-exempt hospital runs a bakery open to the public. The income from that bakery is likely UBTI since it’s unrelated to the hospital’s primary mission (taking care of patients). The hospital would have to pay taxes on all bakery income, reducing its net proceeds.

There’s a laundry list of carveouts to UBTI, such as certain rental income, royalties, dividends, and capital gains. UBTI flows up to tax-exempt LPs from entities taxed as pass-throughs but is “blocked” by entities taxed as C-corporations. The use of leverage (debt) to acquire an investment (or the use of leverage by a pass-through entity owned by a tax-exempt) can convert income or gain from non-UBTI to UBTI.

GENERATING UBTI IN INVESTMENT FUNDS

For investment funds, UBTI issues arise in three common contexts:

- Fund-Level Trade or Business: The fund is directly engaged in a “trade or business,” such as loan origination in a private credit fund. This can be the case if the fund is originating loans and taking an origination fee.

- Pass-Through Portfolio Company Trade or Business: The fund makes an equity investment in a pass-through entity (like an LLC taxed as a partnership) that is engaged in a trade or business. This is less common in venture capital (where companies are typically taxed as C-corporations) and more common in lower-middle-market private equity.

- Leverage: The fund uses leverage, or a portfolio company taxed as a pass-through entity uses leverage.

Needless to say, the UBTI rules are as complex as the range of structures and mechanisms to mitigate their impact.

NINETY-NINE PROBLEMS BUT UBTI DOESN’T NEED TO BE ONE

Investment funds often try to solve UBTI problems for their investors. One common mechanism is to “block” UBTI by creating an entity taxed as an S-corporation through which the tax-exempt LP invests in the fund. You can also put the blocker elsewhere in the fund structure so long as it blocks the tax-exempt’s exposure to the UBTI.

But beware—the blocker entity incurs US corporate federal income tax (currently, a 21 percent rate), and care should be taken not to expose other investors (or the carried interest!) to this tax drag. To accomplish this, your lawyer might set up parallel funds, feeder funds, or alternative investment vehicles (AIVs).

The cost to set up the special structuring for the tax-exempt investors is often borne by the tax-exempt investors themselves, though some funds opt to spread the expenses across the entire (taxable and tax-exempt) LP base.

Note that the usual UBTI regime does not apply to so-called “super tax-exempts” (US governmental entities like public pension funds), which are subject to a different US tax regime and beyond the scope of this book.

Each investment fund should consult its tax advisor about whether the fund is expected to generate UBTI for tax-exempts and if so, tax planning options to address UBTI concerns.

HOW TO HANDLE UBTI CONVERSATIONS WITH LPS

In practice, GPs have three options for how to deal with UBTI situations:

- Do Nothing: Some managers—especially smaller funds and syndications—disclose the UBTI risks to investors and do not undertake special structuring to mitigate UBTI issues. In these cases, tax-exempt LPs can decide whether they’re willing to bear the tax drag UBTI creates or do their own structuring.

- Special Structuring: Some managers—usually of larger funds with more tax-exempt investors—may choose to implement a blocker structure to accommodate tax-exempt investors or engage in other more exotic structuring. This can benefit the tax-exempt investors but requires more legal fees, entity formation, and complexity on the part of the GP.

- Avoid UBTI in the First Place: Some funds, especially venture capital funds, will require all companies to convert to C-corporations before the fund will invest. Among other reasons, this helps eliminate the UBTI concerns for tax-exempt investors.

Sometimes, GPs and tax-exempt LPs do the math and conclude that generating some UBTI is preferable to the expense (e.g., US corporate income tax in a blocker structure) and/or opportunity costs of special structuring or the avoidance of UBTI-producing investments.

In some cases, large LPs might ask for a UBTI covenant. This may require the GP to take “commercially reasonable efforts” (or some other level of efforts) to mitigate UBTI concerns for tax-exempt investors. If you’re a GP that agrees to a UBTI covenant, you’ll need to proactively limit UBTI for your investors. This is often a nice carrot to offer tax-exempt LPs to entice them to invest.

SPECIAL CONSIDERATIONS FOR NON-US INVESTORS

Non-US investors are an increasingly common source of capital. Many funds target Asia, Europe, Latin America, and the Middle East. When raising money offshore, you may want to contact local counsel in the countries where your investors will be. They can help with any securities laws concerns and required filings in offshore jurisdictions. This isn’t a tax point, but it seemed like a good time for a reminder.

Now, on to income effectively connected with a US trade or business, or effectively connected income (ECI).

PASSIVE VS. ACTIVE INCOME (ECI)

Income earned by funds can be roughly split into two buckets for US federal income tax purposes: passive and active. Passive income includes stuff like interest, dividends, royalties, rent, and capital gains. Active income (a.k.a. “ECI”) is essentially operating income from a US business. This is an oversimplification—determining whether income is “passive” or “active” (ECI) involves many nuances and exceptions in practice. But it’s a helpful starting point.

For example, if a foreign entity operates a US-based manufacturing plant, income generated from that plant would count as “active” income. On the other hand, if a non-US person makes a loan to a US-based manufacturing company bearing 10 percent annual interest and owns no equity in the company, the interest is likely exempt passive income.

HOW ARE PASSIVE AND ACTIVE INCOME TAXED FOR NON-US INVESTORS?

The “passive” regime generally applies a flat tax withholding rate on the gross amount of “US-source” passive income—the 2025 default rate is 30 percent unless a special rate or exemption applies. Two common exceptions to this withholding tax include capital gains when a fund sells equity in its portfolio companies and interest income (if the fund is not a loan-origination fund).

By contrast, the “active” (ECI) regime taxes non-US investors on net income (gross income minus expenses) at the same marginal rates that would apply to US individuals or corporations (plus, for non-US corporations, an extra “branch profits” tax to approximate the 30 percent gross withholding tax on dividends that would apply if a US corporation distributed its earnings to a non-US person).

In the tax world, this “active” type of income is typically referred to as “income effectively connected to a US trade or business,” or “ECI,” and non-US investors usually don’t like it for reasons we will explain below!

WHY DO NON-US INVESTORS AVOID ECI?

Like UBTI for tax-exempt investors, non-US investors are often averse to earning ECI. Earning ECI can be “bad” for three main reasons:

- Tax Returns: ECI triggers special US tax-return filing requirements for non-US investors. Most offshore investors don’t love the requirement to file taxes in a new country.

- Investment Returns: The high effective tax rates on ECI (44+ percent on non-US corporate investors) plus applicable US state and local taxes drive down investment returns.

- Compliance: ECI creates additional compliance, administration, and tax liability for investment funds and syndications that have associated tax reporting and withholding obligations and may need to engage in special tax structuring.

Note that the usual ECI regime does not apply to sovereign wealth funds, which are subject to a different US tax regime and beyond the scope of this book (maybe we can talk about it in the next edition).

FIRPTA—THE SPECIAL TAX APPLICABLE TO NON-US INVESTORS IN REAL ESTATE

If you invest in real estate, read this section twice. Then read it again.

Special rules under the Foreign Investment in Real Property Tax Act (FIRPTA), enacted in 1980, classify gains from the sale or disposition of “US real property interests” (USRPIs) as a special category of ECI. Without FIRPTA, these gains would typically be exempt as “passive” income. With FIRPTA, they are generally taxed the same as ECI.

USRPIs include land, buildings, and corporations whose assets consist of 50 percent or more of USRPIs (this calculation is quite complex and, many would argue, over-inclusive!). One notable exception to FIRPTA are interests held solely as a creditor, which includes many real estate loans.

FIRPTA is bad news for similar reasons that ECI generally is bad news (see above)—it taxes income that would otherwise be exempt from US tax at ECI rates, can impose US tax-return filing requirements on the non-US investor in the year FIRPTA gain is recognized, and imposes withholding tax obligations on certain fund or portfolio entities.

GENERATING ECI IN INVESTMENT FUNDS

For investment funds, ECI issues can arise in three common contexts:

- Fund-Level Trade or Business: The fund is directly engaged in a “trade or business,” such as loan origination in a private credit fund. In this case, all interest, fees, and gain from the originated loans may be ECI.

- Pass-Through Portfolio Company Trade or Business: The fund makes an equity investment in a pass-through entity (like an LLC taxed as a partnership) that is engaged in a US trade or business. This is less common in venture capital (where companies are typically taxed as C-corporations) and more common in lower-middle-market private equity.

- US Real Estate: The fund has an ownership interest in US real estate or US companies with enough assets that the IRS treats as real property.

You may notice that, aside from US real estate, this list is eerily similar to the list of UBTI-generating activities discussed above.

HOW TO VALIANTLY PROTECT LPS FROM THE TERRORS OF ECI

Like tax-exempts and UBTI, using a “blocker” (an entity taxed as a US C-corporation) is one common mechanism to block attribution of ECI up to the non-US investor but at the cost of US corporate tax at the blocker level. The UBTI section above discussed this strategy.

However, unlike tax-exempts and UBTI, using blockers to manage ECI has an additional tax wrinkle to manage—in addition to the US corporate tax at the blocker level, distributions of funds from the blocker up to the non-US investors must be structured carefully to mitigate or avoid another level of “passive income” withholding tax on dividends. There are a range of techniques that can be utilized that are beyond the scope of this book, such as adjusting the timing of distributions, selling blocker equity in lieu of receiving blocker distributions, and capitalizing blockers with a combination of equity and debt since the return of debt principal is not typically taxable.

Blockers for non-US investors in real estate funds face additional structural challenges avoiding FIRPTA-generated ECI from certain blocker distributions or gain on the sale of their blocker interest, which may require more special structuring, such as creating one or more offshore vehicles in jurisdictions like the Cayman Islands, British Virgin Islands, or Luxembourg.

As with UBTI and tax-exempts, each investment fund should consult its tax advisor about whether the fund is expected to generate ECI for non-US investors and if so, tax planning options to address ECI concerns.

HOW TO HANDLE ECI CONVERSATIONS WITH LPS

Like with UBTI, GPs have three options for dealing with ECI situations.

- Do Nothing: Some managers—especially smaller funds and syndications—disclose the ECI risks to investors and do not undertake special structuring to mitigate ECI issues. In these cases, non-US LPs can decide whether they’re willing to deal with ECI or do their own structuring.

- Special Structuring: Some managers—larger funds with more non-US investors—may choose to implement a blocker or other special structure to accommodate non-US investors. This can benefit the non-US investors but requires more legal fees, entity formation, and complexity on the part of the GP.

- Avoid ECI in the First Place: Some funds, especially venture capital funds, will require all companies to convert to C-corporations before the fund will invest. Among other reasons, this helps eliminate the ECI concerns for non-US investors. Of course, if you’re a real estate fund, “avoid real estate” isn’t really a viable option, so you’ll likely need to choose options one or two above.

Sometimes, GPs and non-US LPs do the math and conclude that generating some ECI is preferable to the expense (e.g., US corporate income tax in a blocker structure) and/or opportunity costs of special structuring or the avoidance of ECI-producing investments.

In some cases, large LPs might ask for an ECI covenant. This may require the GP to take “commercially reasonable efforts” (or some other level of efforts) to mitigate ECI concerns for non-US investors. If you’re a GP that agrees to an ECI covenant, you’ll need to proactively limit ECI for your investors. This is often a nice carrot to offer non-US LPs to entice them to invest (and some will insist).

⚠ FUND TRAP #16: ADMITTING NON-US INVESTORS INTO A REAL ESTATE FUND WITHOUT SPECIAL STRUCTURING

Newer fund managers might not know about all the ECI and FIRPTA rules. More than once, I’ve come across real estate fund managers with non-US investors…and without special structuring. This is a double whammy for these unsuspecting GPs.

First, their LPs may need to incur taxes and file tax returns they weren’t expecting—this is worse than coal in your stocking. I promise non-US LPs would prefer the coal. In addition, the GP may have tax withholding requirements they weren’t satisfying, adding another layer of complexity and freaking out to their operations.

If you’re considering accepting offshore capital, please make sure to work with a competent tax lawyer who has experience accommodating non-US investors.

WAIVING FEES TO FUND THE GP COMMITMENT

Now, last but not least: a fancy way to structure your GP compensation that may offer tax and liquidity benefits. We discussed the standard taxation of fees and carry earlier in this chapter. Here, you’ll learn about a special mechanism referred to as a “fee waiver” to turbo-charge the tax efficiency of GP compensation. Note that we’re going to say “GP” here for simplicity, but technically the fee is often waived by the fund’s ManCo.

A cautionary note before we get started. Even when structured carefully, fee waivers are not free from tax risk and could be successfully challenged by the IRS given certain grey areas of the tax law. Tread carefully, and work with a competent tax lawyer.

WHAT IS A FEE WAIVER?

A fee waiver is…the waiver of a fee. Typically, the fee being waived is either a fund’s asset management fee or an acquisition fee. Basically, the GP foregoes a fee they’re otherwise entitled to, and, in exchange, they get additional equity in the fund or syndication.

Fee waivers aim to accomplish two primary tax objectives by “trading” waived fees for something called a “profits interest” for tax purposes:

- Defer Taxation: Defer taxation of fee income. Instead of paying taxes on fee income now, you are taxed later.

- Tax Character: Convert ordinary income from fees into dividends or capital gains taxed at preferential rates.

HOW IS GP COMPENSATION TAXED WITHOUT USING A FEE WAIVER?

On one hand, management fees (and other fees, such as acquisition fees) are normally taxed as ordinary income as the fund pays them (e.g., quarterly after the fund’s initial close).

On the other hand, carried interest is taxed at the time it is earned—typically after the fund earns enough income to return capital to LPs (plus potentially a preferred return).

The tax character of the carried interest (i.e., whether it’s ordinary income or capital gains) depends on the tax character of the income or gain earned by the fund. For many funds, the carried interest is taxed at lower rates than ordinary income (e.g., capital gains or dividends).

HOW DOES THE FEE WAIVER WORK?

In a typical fee waiver, the GP agrees to irrevocably (no take-backs!) waive a portion (or all) of the management fee (or acquisition fee). This election should be made on the initial closing date of the fund or syndication.

In exchange, the GP is treated as having contributed the amount of the fee waived as a “deemed” capital contribution to the fund. In other words, they get a type of equity in the fund intended to be a “profits interest” for US federal income tax purposes.

But…it’s not all sunshine and rainbows. There’s no free lunch!

THE RISKS AND NITTY GRITTY OF FEE WAIVERS

The GP does not get their “deemed” capital contribution (the amount of the waived fee) returned when the other LPs get their capital contributions returned. Instead, they get the deemed contribution amount back on a priority basis from the fund’s profits after the return of capital to the LPs. Note that the GP takes a true economic risk here, which is the basis for the “profits interest” tax position. If the fund is not profitable, the GP waives the fee but does not get the benefit of the deemed contribution. They waived the fee for nothing (and can’t take it back).

After the priority return of the deemed contribution amount to the GP (after the fund is profitable), the GP then receives a return on the deemed contribution as if it were a normal capital contribution. This is in addition to the carried interest they would otherwise earn and any return on the GP’s actual cash capital contribution.

Like the carried interest, amounts earned through the fee waiver are taxed based on the characterization of the underlying income generating the return. For a fund like a venture fund, the character is typically long-term capital gains or QSBS, both of which are taxed preferentially compared to ordinary income (as with the carry, special holding-period rules apply).

SHOULD GPS USE FEE WAIVERS?

As you’ve seen, waiving fees can be a tantalizing proposition. In addition to the exciting tax benefits, waiving fees can help GPs with cash flow. Instead of coming up with a cash GP commitment now, they can use the fee waiver.

However, in addition to the tax risks and the economic risk that the fund might not generate enough profit to earn back the waived fees, there are a few drawbacks to using fee waivers. For example, some LPs might prefer you fund your GP commitment with cash. In addition, the fee waiver mechanism is complex, and your service providers (lawyer, administrator, CPA) might not understand it. Finally, you might actually need the full management/acquisition fees to keep the lights on at the GP.

Congratulations! You made it through an entire chapter on taxes (and, happily, this entire book). You now understand more about investment funds and syndications than many GPs. Certainly enough to get started.

More Fundamentals Chapters

Let's Build Something Together

Please provide some background on yourself, your track record (if applicable), and your goals. We're excited to get started.