Do You Want a “Closed-End” Fund or an Evergreen “Open-End” Fund?

Do You Want a “Closed-End” Fund or an Evergreen “Open-End” Fund?**

In Chapter 4, we compared single-asset syndications and multi-asset funds. If you’ve 100 percent decided you want to syndicate deal by deal, you can skip this chapter. However, if you want to be a fund manager (or aren’t sure one way or the other yet), this chapter is important.

Here, we’ll discuss closed-end and open-end investment funds and how they differ and then walk through the full life-cycle of a typical closed-end fund. We won’t walk through the life of an open-end fund because—as you’ll learn—open-end funds have a perpetual duration without distinct phases.

CLOSED-END INVESTMENT FUNDS

Let’s discuss the key features of a typical closed-end fund.

1. Defined Fundraising Period

In closed-end funds, you generally have twelve to eighteen months (or longer if approved by LPs) to continue raising capital after the fund’s initial closing date (the day you admit your first investors). When that period ends, the fund’s “final closing date” occurs, and the fund can’t accept new investors. As of the final closing date, the die is cast. No more fundraising (thank goodness).

2. Defined Investment Period

Closed-end funds usually have an “investment period” when the fund makes investments in new assets. The investment period is typically the first half of a fund’s life. After the investment period has ended, the fund can still call capital for limited purposes, such as:

- Paying fund expenses (including repaying debt)

- Follow-on investments in existing companies

- Repairs or improvements to existing properties

- Exercising options or warrants the fund already holds

- Investments that were in process as of the end of the investment period

- Investments specifically approved by the LPs

In addition, a few other things typically happen when a closed-end fund’s investment period ends. For example, the management fee is normally reduced (see Chapter 2), the GP can usually start the next fund (often called a “successor fund”), and the GP’s “time commitment” requirement typically decreases (usually from spending “substantially all” of their time on the fund to remaining “actively involved”).

3. Defined Fund Term

Closed-end funds usually have a set life. Many funds last ten years. Typically, the GP can extend the fund’s life for a year or two, and the LPs can agree to further extend the fund’s life.

In some funds, the LPs can terminate the fund early. The following are example provisions for terminating a fund:

- 80 percent of the LPs can end the fund’s life for any reason

- 51 percent of the LPs can end the fund’s life if the GP commits a “bad act” (such as fraud or gross negligence)

These LP termination rights are often negotiated by LPs and the GP.

4. LPs Can’t Withdraw Their Money

In a closed-end fund, the LPs are locked in! Subject to narrow exceptions (or the good graces of the GP), investors aren’t allowed to withdraw money. They get their money back over time as the fund (hopefully) makes distributions or when the fund sells its assets and distributes cash at the end of its life.

5. Fund Economics Are “Distribution-Based”

This is a technical point, but economics like carried interest are based on “distributions” instead of capital account appreciation. For example, a profit split might look like this:

- First, LPs get their money back

- Second, LPs get a preferred return

- Thereafter, the GP gets 20 percent and LPs get 80 percent

The GP’s right to carried interest is based on realized transactions (e.g., sales/refinances or cash flow). If the value of the fund’s assets rises but nothing else happens (such as a sale or refinance), the GP would not typically earn carried interest in a closed-end fund.

OPEN-END INVESTMENT FUNDS

Open-end funds are an entirely different beast. Let’s look at their key features and how they differ from closed-end funds.

1. Unlimited Fundraising Period

Unlike closed-end funds, open-end funds can fundraise forever. New investors are often admitted monthly or quarterly, and they contribute money into their capital accounts.

If the fund has units (shares of equity), it will have a mechanism for determining how many units an investor gets upon contributing capital.

For example, a fund may determine the price per unit by dividing the fund’s net asset value by the number of units. When a new LP joins (or an existing LP increases its investment), it receives the number of units determined by dividing its capital contribution by the current price per unit.

Other funds are not “unitized”—in these funds, LPs merely get an increase in their capital account when they contribute additional funds.

2. No Investment Period

Open-end funds don’t usually have an investment period. They can make investments in new businesses, products, or properties whenever they want.

3. Unlimited Fund Term

Open-end funds typically have no set term. They can live forever (in theory).

4. LPs Can Withdraw Their Money

If an open-end fund lasts forever, how do LPs get their money back? In open-end funds, LPs can usually withdraw their money, subject to the restrictions discussed below.

Lockup Periods

Open-end funds often have a lockup period during which LPs are not allowed to withdraw their money. In a hedge fund (or any other fund with highly liquid assets), the lockup period might be a year or two. In an illiquid asset class, like real estate or private equity, the lockup period might be much longer (two to five years or more).

If you’re buying illiquid assets, you don’t want people to withdraw immediately. It might be hard to raise the cash to redeem the withdrawing investors without fire-selling the fund’s assets and harming the remaining LPs.

Many funds have a separate lockup period for each capital contribution an LP makes. So, if an LP puts in $100 on January 1, 2025, and $200 on January 1, 2026, those two investments would have different lockup periods.

Gates

Once the lockup period ends, LPs can start withdrawing money. However, most open-end funds also have a gate, which limits the amount of withdrawals. There are two main types of gates:

- Fund-Wide Gates. For example, no more than 20 percent of the fund’s assets can be withdrawn in any calendar year.

- Investor-by-Investor Gates. For example, an LP may not withdraw more than 25 percent of its capital account in any single quarter.

Typically, any outstanding withdrawal requests (if the gate stops any withdrawals) are rolled to the next withdrawal date. As with lockup periods, illiquid asset classes tend to have stricter gates (meaning investors are subject to lower withdrawal thresholds).

5. Fund Economics Are Often “Capital Account–Based”

In many open-end funds, the GP’s carried interest is based on an LP’s capital account, not distributions. What does that mean in plain English?

If a fund holds shares of Apple at $100 and the shares increase to $150, the GP can take carried interest even if the fund doesn’t sell the Apple shares (and the fund makes no distributions). The capital accounts increase alongside Apple’s appreciation, and that’s enough for the GP to receive an incentive allocation of carried interest.

In some cases, open-end funds might be distribution-based. Distribution-based economics may be more suitable for illiquid asset classes (like real estate), where valuing the underlying investments isn’t as simple as it is for assets like public equities.

⚠ FUND TRAP #5: MISMANAGING LIQUIDITY IN OPEN-END FUNDS

Open-end funds are becoming more popular than Taylor Swift (and sing at least as well—just kidding; please don’t yell at me). Increasingly, GPs in private equity and real estate want the flexibility to hold high-quality assets for the long term without needing to sell.

While this can be a successful strategy, GPs seeking to raise open-end funds in illiquid asset classes should work with their attorney to craft appropriate lockup periods and gates to prevent a liquidity crunch in the event LPs start wanting to withdraw.

While a one-year lockup period and 25 percent quarterly gate might work for a hedge fund, an open-end real estate or private equity fund might want to consider significantly more restrictive lockup periods and gates. Otherwise, the fund might have to sell assets at discounted prices to meet LP redemption requests (due to the inherent illiquidity of the underlying assets).

Funds really do enforce these limits. Famously, the Blackstone REIT (dubbed BREIT) imposed withdrawal restrictions on its investors for over a year starting in November 2022. Even the big players need help managing liquidity!

WHAT’S BETTER: CLOSED-END OR OPEN-END?

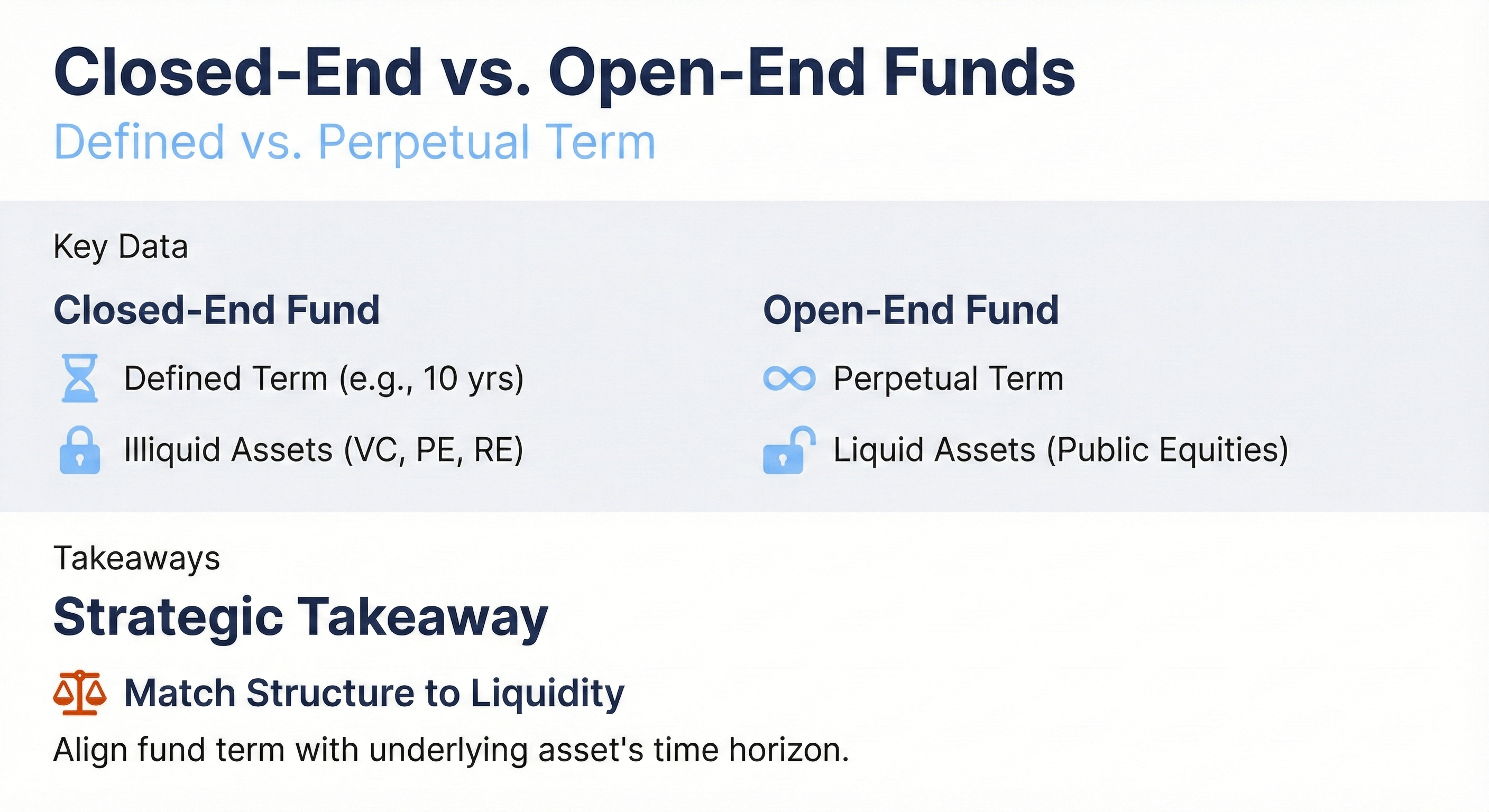

Neither is inherently good or bad, better or worse. However, industry standards are as follows:

- Private equity funds are usually closed-end

- Venture capital funds are usually closed-end

- Real estate funds are usually closed-end, but some asset classes (especially buy-and-hold cash-flow strategies) may be open-end

- Debt funds may be closed-end or open-end

- Public equities funds are usually open-end

In summary:

- Illiquid strategies are usually closed-end

- Liquid strategies are usually open-end

If you want an open-end fund with an illiquid strategy, you may want to impose strict lockup periods and gates.

FULL LIFECYCLE OF A CLOSED-END INVESTMENT FUND

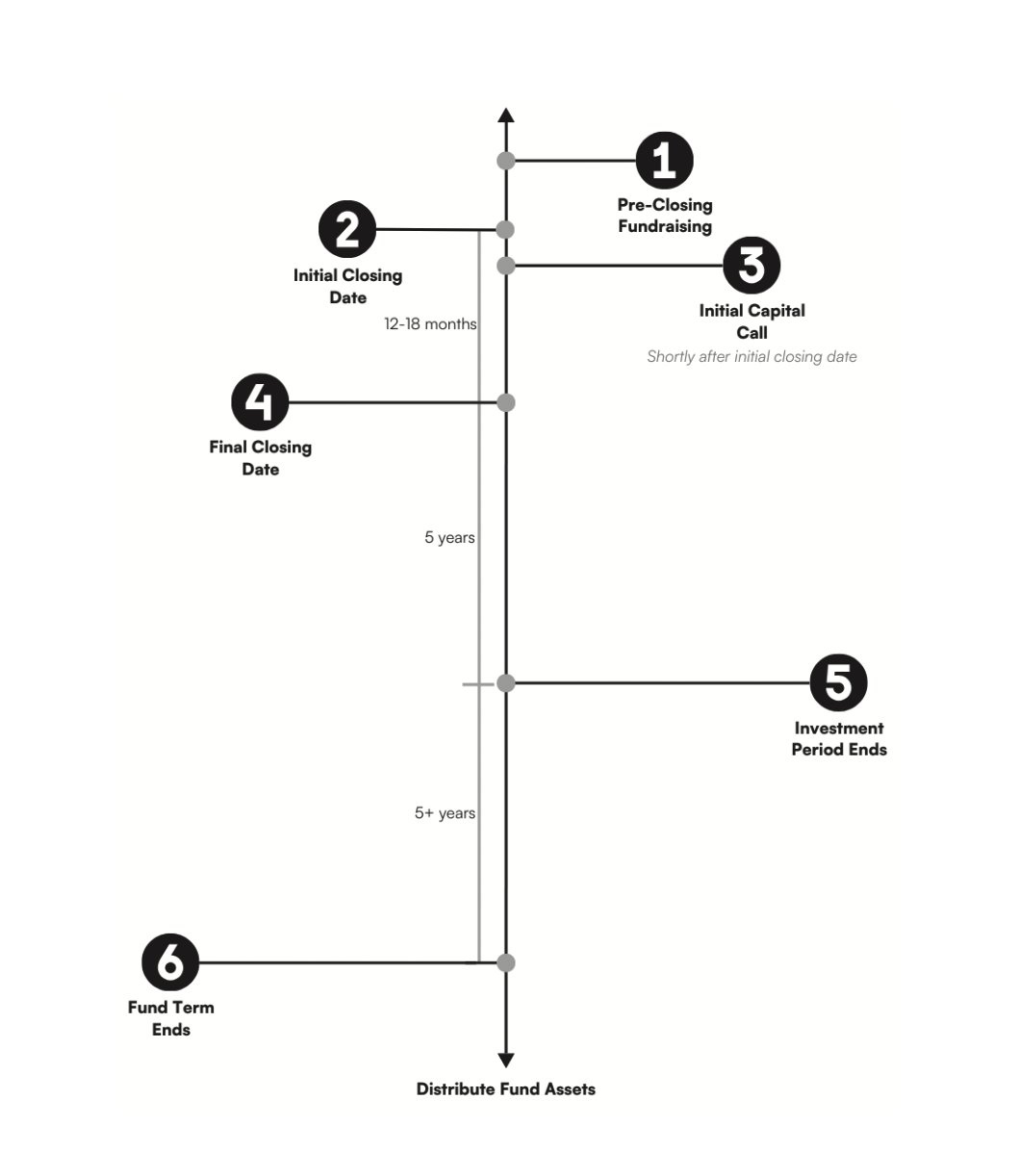

Now that we understand the difference between closed-end and open-end funds, let’s learn the six critical phases of a closed-end fund’s life.

1. Pre-Closing Fundraising

This is summarized in Chapter 1. You work with your lawyer to get your fund documents prepared and then send them to potential LPs. Chapter 12 explains who you’re allowed to solicit for investment.

2. Initial Closing Date

The initial closing date is a big deal for an investment fund. It’s the day you counter-sign subscription documents and admit the first LPs. The mechanics of the initial closing are discussed in Chapter 10.

3. Initial Capital Call

Show me the money! Once the fund holds an initial closing, you can officially call capital from the LPs. Calling capital involves the GP sending a notice to the LPs asking for money. We’ll discuss capital calls in detail in Chapter 11.

4. Final Closing Date

Most investment funds don’t raise their full target fund size at the initial closing. For example, an investment fund may have a $100 million target fund size but only close on $30 million of commitments at the initial closing. Then, it raises the remaining $70 million over the next year or two.

Most closed-end funds have a cutoff date for when fundraising must stop. A typical fundraising period lasts twelve months from the initial closing date with an optional six-month extension at the GP’s discretion. This cutoff can typically be further extended if the LPs agree.

Until the final closing date, GPs often invest and fundraise simultaneously. While this is a lot of work, it enables the fund to show potential LPs a track record of actual investments, which may aid in fundraising.

5. Investment Period Ends

As discussed earlier in this chapter, closed-end funds typically have an investment period during which the fund can make new investments. The investment period is usually half the fund’s life (e.g., five years in a standard ten-year fund). As discussed in Chapter 2, the management fee earned by the GP/ManCo typically decreases at the end of the investment period.

6. Fund Term Ends

All good things must come to an end. Eventually, the fund’s term expires, at which point the fund liquidates, sells off any remaining investments, and distributes the cash to the LPs and the GP pursuant to the fund’s distribution waterfall.

In some cases, the GP (and some LPs) might not want to sell the assets. The assets are great! If so, the GP may form a continuation fund to purchase the best assets from the terminating fund. In many cases, LPs can elect to tag along and keep the party going. The continuation fund might also accept new investors who weren’t in the original fund.

Once you decide whether to have an open-end fund or a closed-end fund, you need to get specific. In the next chapter, you’ll learn how to build out a fulsome term sheet for your fund.

More Fundamentals Chapters

Let's Build Something Together

Please provide some background on yourself, your track record (if applicable), and your goals. We're excited to get started.