The Investment Company Act of 1940

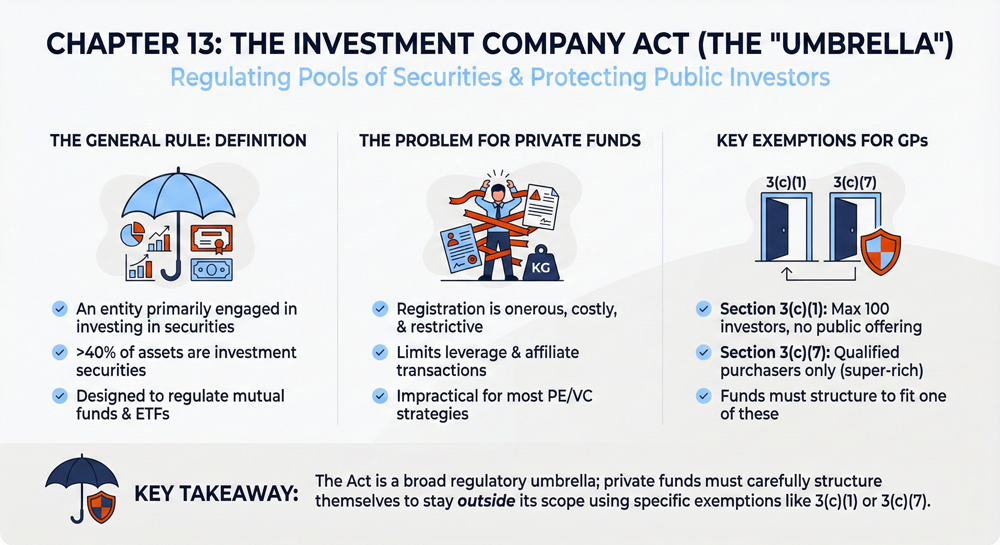

In the last chapter, we discussed the Securities Act, which applies to essentially all investment funds and syndications. In this chapter, you’ll learn about the Investment Company Act.

WHO DOES THE INVESTMENT COMPANY ACT APPLY TO?

The Investment Company Act applies to investment companies (big surprise). The statutory definition of “investment company” according to Title 15 of the US Code is as follows:⁶

(a) Definitions

(1) When used in this subchapter, “investment company” means any issuer which—

(A) is or holds itself out as being engaged primarily, or proposes to engage primarily, in the business of investing, reinvesting, or trading in securities;

(B) is engaged or proposes to engage in the business of issuing face-amount certificates of the installment type, or has been engaged in such business and has any such certificate outstanding; or

(C) is engaged or proposes to engage in the business of investing, reinvesting, owning, holding, or trading in securities, and owns or proposes to acquire investment securities having a value exceeding 40 per centum of the value of such issuer’s total assets (exclusive of Government securities and cash items) on an unconsolidated basis.

(2) As used in this section, “investment securities” includes all securities except (A) Government securities, (B) securities issued by employees’ securities companies, and (C) securities issued by majority-owned subsidiaries of the owner which (i) are not investment companies, and (ii) are not relying on the exception from the definition of investment company in paragraph (1) or (7) of subsection (c).

In short, the two main ways to become classified as an investment company are:

• Primarily Investing in Securities: The business is primarily engaged in investing in securities (or holds itself out as being primarily engaged in investing in securities).

• 40 Percent Asset Test: Even if the business isn’t “primarily” investing in securities, it can be considered an investment company if at least 40 percent of the business’s assets are securities (excluding government securities).

Private equity funds, venture capital funds, and hedge funds are typical examples of investment companies.

WHAT ABOUT REAL ESTATE FUNDS AND SYNDICATIONS?

Real estate (buildings, land, etc.) is not a security. As a result, pure real estate funds and syndications are typically not considered investment companies and do not need to deal with the Investment Company Act.

However, a real estate fund-of-funds does invest in securities (i.e., the securities of the underlying fund) and would typically be considered an investment company. A fund formed to invest in passive joint-venture interests may also be considered an investment company. Determining classification under the Investment Company Act involves a case-by-case analysis of the facts of each particular situation. Check with your lawyer!

WHAT ABOUT DEBT FUNDS AND SYNDICATIONS?

Under the Securities Act (discussed in Chapter 12), many debt instruments are not securities. However, it’s generally understood that most debt instruments are securities for the purposes of the Investment Company Act and the Investment Advisers Act (discussed in Chapter 14).

Counterintuitively, many debt funds are considered investment companies even though the funds themselves might not be investing in things considered securities under the Securities Act. Again, this will involve a case-by-case analysis by your lawyer.

WHAT HAPPENS IF YOU’RE AN INVESTMENT COMPANY?

Investment companies without an exemption are subject to significant SEC regulation. These non-exempt investment companies—such as mutual funds and exchange-traded funds (ETFs)—are often referred to as “40 Act” funds.

Lots of lawyer time and legal bills (and headaches) are required to manage and maintain 40 Act funds. Most small and medium-sized funds and syndications can’t support the weight of these regulations. Luckily, there are several statutory exemptions from registering as a 40 Act fund.

The most common exemptions for private funds and syndications are:

• 3(c)(1): The “100 Investor” exemption

• 3(c)(7): The “Qualified Purchaser” exemption

• 3(c)(5)(C): The “Real Estate” exemption

Let’s examine each in turn.

3(c)(1) — THE “100 INVESTOR” EXEMPTION

One way to be exempt from the onerous 40 Act requirements is to limit your fund or syndication to one hundred investors or fewer. Simple enough? Not so fast. Counting is harder than you might think! Some investors count as more than one investor.

The rules are complicated enough that we can’t get into them all here, but here are some examples:

• Newly-Formed LLC: If people form an LLC just to invest in your fund or syndication, you may need to count all the owners of that LLC.

• Fund-of-Funds: If a fund-of-funds is more than 10 percent of your fund’s equity, you may need to count all the fund-of-funds’ investors.

• 40 Percent Test: If more than 40 percent of an entity’s assets are invested in your fund/syndication, you may need to count all the entity’s investors.

Your investment fund’s sub docs should include questions for your investors regarding 3(c)(1) “investor counting.” Your lawyer will help you review investors’ answers to ensure you have a good 3(c)(1) exemption from the Investment Company Act.

⚠ FUND TRAP #13: ACCEPTING SMALL INVESTORS WHO FILL UP YOUR 3(c)(1) SLOTS

Early in the fundraising process, GPs often take whatever money they can get. Twenty-five thousand dollars here. Fifty thousand dollars there. It’s understandable. They want to get the ball rolling. (I once saw an LP try to invest $2,000.)

However, 3(c)(1) funds should be careful about accepting smaller checks, especially when the investing entities count as more than one investor for 3(c)(1) purposes. For example, you might have a potential LP that wants to invest $100,000—your fund’s minimum. However, the potential LP is an LLC newly formed by eight friends to invest in your fund. If admitted, the LLC would take up eight slots for 3(c)(1) purposes—contributing just $12,500 per slot. Is it worth admitting them?

I’ve seen this happen to fund managers before: they were overzealous about accepting as much money as possible and then ran into their one-hundred-investor cap sooner than expected. Your lawyer should explicitly let you know when any investor would count as more than one for 3(c)(1) purposes. Then, you can make the judgment call as to whether the LP is worth admitting.

NOTE ON SMALL VENTURE CAPITAL FUNDS

Venture capital funds have special 3(c)(1) thresholds. If the fund has less than $12 million in commitments (recently raised from $10 million), the fund can have up to 250 investors. There have also been political rumblings about increasing these thresholds even further. The venture capital lobby must be powerful (see Chapter 14 for more on this). I’ll leave it to you to decide for yourself whether you would want to run a $12 million fund with 250 investors.

3(c)(7) — THE “QUALIFIED PURCHASER” EXEMPTION

An investment company can also be exempt from the Investment Company Act if 100 percent of its investors (other than members of the GP team) are “qualified purchasers” (i.e., really fancy people). The bar to becoming a qualified purchaser is much higher than the accredited investor threshold. Generally, individuals must have investment assets of at least $5 million and entities must have investment assets of at least $25 million to be considered a qualified purchaser.

KNOWLEDGEABLE EMPLOYEES

You may have noticed that “other than members of the GP team” language up there. What’s that about? Well, the GP and their core team (called “knowledgeable employees”) can invest in a 3(c)(7) fund even if they aren’t qualified purchasers. The Code of Federal Regulations (CFR) states the following:⁷

(b) For purposes of determining the number of beneficial owners of a Section 3(c)(1) Company, and whether the outstanding securities of a Section 3(c)(7) Company are owned exclusively by qualified purchasers, there shall be excluded securities beneficially owned by:

(1) A person who at the time such securities were acquired was a Knowledgeable Employee of such Company;

(2) A company owned exclusively by Knowledgeable Employees;

(3) Any person who acquires securities originally acquired by a Knowledgeable Employee in accordance with this section, provided that such securities were acquired by such person in accordance with §270.3c-6

Note that only high-level employees count. Lower-level staff who are not part of the investment decision-making process are not considered knowledgeable employees. See the text from the CFR below:⁸

(4) The term Knowledgeable Employee with respect to any Covered Company means any natural person who is:

(i) An Executive Officer, director, trustee, general partner, advisory board member, or person serving in a similar capacity, of the Covered Company or an Affiliated Management Person of the Covered Company; or

(ii) An employee of the Covered Company or an Affiliated Management Person of the Covered Company (other than an employee performing solely clerical, secretarial or administrative functions with regard to such company or its investments) who, in connection with his or her regular functions or duties, participates in the investment activities of such Covered Company, other Covered Companies, or investment companies the investment activities of which are managed by such Affiliated Management Person of the Covered Company, provided that such employee has been performing such functions and duties for or on behalf of the Covered Company or the Affiliated Management Person of the Covered Company, or substantially similar functions or duties for or on behalf of another company for at least 12 months.

By the way, knowledgeable employees are also excluded from the one-hundred-investor limit in 3(c)(1).

PARALLEL FUNDS

Does a cap of one hundred investors seem too restrictive? Upset that you have some investors who are not qualified purchasers? There’s gotta be a better way! Well, there’s a solution: parallel funds.

Parallel funds are side-by-side 3(c)(1) and 3(c)(7) funds. You fill one fund with no more than one hundred investors and the other with only qualified purchasers. Then, when you invest in underlying assets, each fund contributes a portion of the capital required. In some cases, you can form an “aggregator” entity jointly owned by the 3(c)(1) fund and the 3(c)(7) fund.

It goes without saying that you should work with a lawyer if you want to raise parallel funds (but I said it anyway).

3(c)(5)(C) — THE “REAL ESTATE” EXEMPTION

One last exemption to discuss! We learned above that pure real estate funds are often outside the reach of the Investment Company Act. But…what if you’re a real estate debt fund? What if some of your assets are real estate equity and some are real estate debt? What if some of your assets are passive interests in other funds, syndications, or joint ventures?

Then, you need 3(c)(5)(C), which exempts funds “purchasing or otherwise acquiring mortgages and other liens on and interest in real estate.”⁹ To rely on 3(c)(5)(C), the fund must meet the following requirements:¹⁰

- At least 55 percent of the fund’s assets must consist of “qualifying investments.” A qualifying investment is an actual interest in real estate or a loan/lien fully secured by real estate.

- At least 80 percent of the fund’s assets must consist of qualifying assets or “real estate-type interests.”

- No more than 20 percent of the fund’s total assets can consist of assets that have no relationship to real estate.

As usual, this is something to talk to your lawyer about. The analysis can get tricky.

NOTE ON OPEN-END FUNDS

3(c)(5)(C) is not available to funds “in the business of issuing redeemable securities.”¹¹ “Redeemable securities” are defined in Title 15 of the US Code as follows:¹²

“Redeemable security” means any security, other than short-term paper, under the terms of which the holder, upon its presentation to the issuer or to a person designated by the issuer, is entitled (whether absolutely or only out of surplus) to receive approximately his proportionate share of the issuer’s current net assets, or the cash equivalent thereof.

Financial products like mutual funds and ETFs are typically redeemable securities—it’s very easy to sell shares in an ETF. Interests in typical hedge funds with easy liquidity are also likely redeemable securities. However, there’s some gray area around whether open-end real estate–related funds issue redeemable securities. In fact, two of the big law firms I’ve worked at have disagreed on this point!

In general, the more restrictions imposed on LP withdrawals/redemptions, the less likely it is the fund will be deemed to have redeemable securities. If you need to rely on 3(c)(5)(C), you may want to make LP redemptions at the GP’s discretion (or require several conditions on withdrawal to be satisfied before redeeming). Check out Chapter 5 for a discussion on lockups and gates to manage liquidity and withdrawals.

NOTE ON 3(c)(5)(C) VS. 3(c)(1) AND 3(c)(7)

If you have the choice of relying on 3(c)(1), 3(c)(7), or 3(c)(5)(C), you may want to choose 3(c)(5)(C). If recently killed private fund rules (implemented by the SEC and struck down by the Fifth Circuit Court of Appeals) were revived, many of the new regulations would apply to 3(c)(1) funds and 3(c)(7) funds but not 3(c)(5)(C) funds. Perhaps the SEC will give up and not try to revive these comprehensive reforms. But you never know.

Similarly, the new FinCEN KYC/AML rules mentioned in Chapter 10 will apply to 3(c)(1) funds and 3(c)(7) funds but do not look like they’ll apply to 3(c)(5)(C) funds. If you can avoid investing in real estate “securities” (and stick to pure dirt and buildings), it may make your life easier from a regulatory perspective.

Next up, we’ll discuss the Investment Company Act’s fraternal twin—the Investment Advisers Act.

More Fundamentals Chapters

Let's Build Something Together

Please provide some background on yourself, your track record (if applicable), and your goals. We're excited to get started.